“Because it’s there,” is how the British mountaineer George Mallory answered a journalist who asked why he was attempting to climb Everest back in the 1920s. It’s a neat answer, which many doubt Mallory even said, but it’s an apt one. And, as the crowds cluttering up the slopes this May illustrated, as long as Everest is there, people will want to climb her.

The pictures of Everest that circulated in May showed lines of climbers waiting to ascend Everest’s peak; Gortex-clad adventurers who had at least US$35,000 to spend (although the average cost is twice that) to complete the climb. The photos were taken close to the summit in May, traditionally climbing season, in which there are usually two weeks of calm weather to attempt to get to the top. Eleven people died that month, partly due to inclement weather: there were fewer days on which to attempt the climb, leading to more people crowding the slopes on the clear days.

The overcrowding is nothing new. In the early Nineties the Nepali authorities tried to curb the increasing numbers by raising fees. In 1991, a climbing permit cost $2,300 for a team of any size. The following year, the fee was raised again to $10,000 for a team of nine climbers. That didn’t stem the numbers and by 1993, on the 40th anniversary of the first ascent, 15 expeditions, featuring nearly 300 climbers made the climb. Later that year, the authorities raised the fees again, to an eye watering $50,000 for a five-person team and $10,000 for each additional climber, of which only two were allowed. They also only allowed four expeditions per season.

Unfortunately for the Nepali government, there is another way to climb Everest – via Tibet, where there were fewer qualms about allowing as many expeditions in as wanted to climb. They also only charged $15,000 for a team of any size. Soon, under pressure from a Sherpa community dependent on the climbing industry, the Nepali authorities backed down, and cancelled the four expedition limit, but not without hiking the prices again to $70,000 for a seven-climber team, plus $10,000 for each additional climber.

And as the slopes got more crowded, and the type of climber changed from the hardy adventurer to the rich forty- and fifty-something who wanted to tick it off their bucket list, so some of the stories got downright bizarre. In John Krakauer’s seminal tale of his own Everest attempt, Into Thin Air, he quotes one Everest guide who recalled that some climbers have sued their guides when they failed to reach the summit. “Occasionally you’ll get a client who thinks he’s bought a guaranteed ticket to the summit,” said the experienced Everest guide, Peter Athans. “Some people don’t realise that an Everest expedition can’t be run like a Swiss train.”

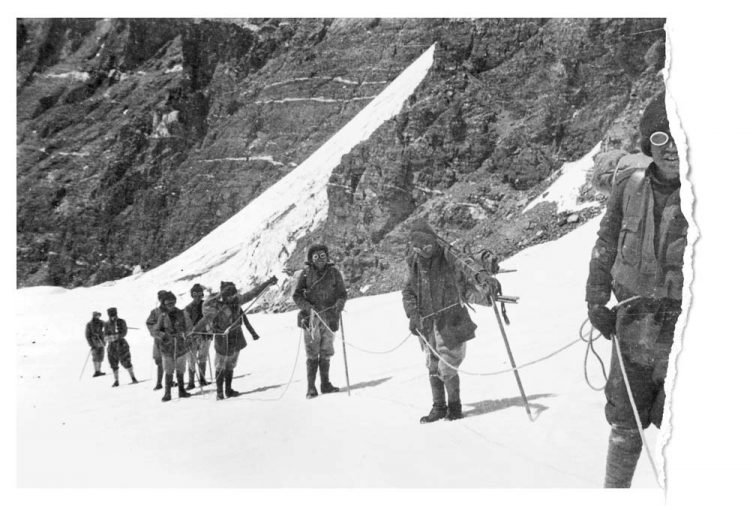

Indeed the new breed of Everest climber, even back in 1993, were a world away from the rugged, slightly bonkers men who attempt the first climbs back in the 1950s. The first men – New Zealander Edmund Hilary and his Sherpa guide, Tenzing Norgay – conquered Everest on the morning of May 29th, 1953. The news, when it spread around the world, was akin to the moon landing, a ‘where were you?’ event that takes place once a generation. Norgay and Hilary were not the first men to attempt the climb; since the mountain was ‘discovered’ by an Indian civil servant in 1852. It would take more than a century, 15 separate expeditions and 24 deaths, before the successful 1953 climb.

What hasn’t changed since those early days is the mountain itself and the dangers attempting to climb it brings: those are myriad. The first and most obvious is altitude sickness, which starts to affect those 2,500 metres above sea level. The most common symptoms are headaches, tiredness, vomiting, dizziness and an inability to sleep. Everest’s base camp is nearly 5,400 metres above sea level, which is why it’s recommended climbers spend at least six weeks acclimatising, moving up and back down the mountain in order to be ready for the summit. The summit and the 1,000 metres below it are known as the ‘death zone’ and it’s here that most of the 308 climbers who have died on the mountain have been.

It’s where altitude sickness turns into HAPE (high altitude pulmonary edema); where the lack of oxygen means fluid is leaked into the lungs and a cough that can crack ribs. Blood samples taken from four mountaineers in the death zone in 2007 revealed they were surviving on 25 per cent of the oxygen they needed at sea level. At that height, the body stops healing and cuts turn into festering sores, while food no longer breaks down, meaning the body consumes itself for sustenance. In order to combat this, most expeditions establish a series of camps above Base Camp, moving food, equipment and people up and down until the climbers are ensconced on the South Coll, a ridge about 900 metres below the summit. It’s actually possible to reach that summit without oxygen, but it’s happened incredibly rarely.

In May 1978, the renowned Austrian mountaineer Reinhold Messner and another Austrian, Peter Habeler, made it to the top without oxygen (although of course many of the local Sherpas had already done the same). Some in the climbing community hailed the feat as the first “true” ascent of Everest. Two years later Messner did it again, this time alone, from the Tibetan side of the mountain. “I was in continual agony,” he said. “Never in my life have I been so tired.”

In 1980, the mountain was still the preserve of the mountaineering elite, but that was all about to change. One of the first ‘commercial’ mountaineering groups was run by Adventure Consultants, founded by the New Zealand climber Guy Cotter, who has himself summited Everest five times. “Prior to that period it was either national teams or sponsored expeditions that were there to attempt Everest,” he says. “In general the leaders on those expeditions had very little or no experience running expeditions and serious accidents and low success rates were the norm. A person who raised the sponsorship often ran the expedition and pulled in a bunch of star climbers who weren’t there as a team but more likely a group of individuals all vying to be the one who reached the summit.”

As more and more companies were set up, the mountain opened up to those other than the climbing elite: wealthy adventurers who wanted to tick summiting Everest off their bucket list. The criticism that these groups get irks Cotter. “Expeditions to Everest have always been commercial,” he says. “Due to some weird reverse-racist type thinking climbing Everest was only deemed commercial when Western climbers started charging for their services while thousands of Nepali were being paid to work on expeditions since the first attempts.”

In the Eighties and Nineties, it was still difficult for an inexperienced climber to join a tour – these days anyone can research and choose them online, often with unintended consequences. “People are now internet shopping for an Everest expedition and find it very hard for them to determine the value proposition offered by a professional organisation with experienced qualified guides versus one that offers less,” Cotter adds. “I think many people recognise after they get home and have their hands or feet amputated through frost-bite that the cost difference (of say $20,000) between what they paid for their cheap expedition and a professional outfit is negligible.”

Of course, for those that reach the top, frostbite is often the least of their worries. Climbers who spend too long on the summit run the risk of running out of oxygen on the way down: the summit is only the half-way point. Many climbers run out of oxygen between the top and Base Camp and lapse into a dream like sleep on the slopes, never to awake.

Somewhat lost among the hand-wringing that took place after the May deaths is the role of the Sherpas themselves, a group of people who rely on the mountain for their livelihood. Indeed, the list of those who have climbed the mountain is dominated by Sherpas, including five who have summited more than twenty times each. The narrative is so often dominated by Western climbers it’s easy to ignore how important the mountain is to the local Sherpa community.

“Sagarmartha is a sacred mountain to the local Sherpa communities,” says John Loof, General Manager of the Himalayan Trust in New Zealand, a charity established by Edmund Hilary. “Tourism has brought incredible change for local communities. But climbing tourism has also brought great tragedy. Around one-third of all those who have died climbing Everest are Sherpa. This takes a very heavy toll on families and communities. I met a young Sherpa woman recently who insisted her husband work as a trekking guide, which – while it pays less than a high-altitude climbing guide – also has a fraction of the hazards.”

So, what does the future hold? It’s hard to see the Nepali government handing out less permits – it provides much needed investment into the country and keeps the Sherpas happy. This year 891 climbers reached the summit; could we be far off seeing 1,000 make it to the top? And if they did, so what? These climbers know the risks – each one of them made the decision to attempt to summit the peak, knowing that it still is one of the riskiest human endeavours out there. Others say that something needs to be done, arguing local greed is putting people’s lives at risk.

“There are too many inexperienced people there who slow everyone down,” Guy Cotter says. “Indian nationals who are in the military or police will get a promotion if they summit Everest, and their state will give them land or money if they succeed, so there is a financial incentive as well as the prestige they will earn back home if they do summit.” The way local tour operators sell packages has also changed, Cotter says.

“In years past a local operator would provide services to national teams or guided expeditions such as ours but many of them now sell ‘tickets’ on their expeditions to anyone who will pay without having a duty of care for their well-being and they have the highest number of accidents and fatalities. What needs to change is that climbers need to have proved themselves on progressively higher mountains before they get accepted onto an Everest expedition. As it stands the situation is similar to what it would be like if anyone could climb into a Formula 1 car and race with no prior racing experience.”

The Himalayan Trust would like to see the focus move from just Everest to the entire local region. “While it is understandable that climbing Everest is on many people’s bucket list, well-managed tourism could see other spectacular trekking routes developed and serviced, to spread the tourism dollar to more communities,” says John Loof. “[We would like to see] more support for well-managed, community development work in the region such as support for education as a route out of poverty, investing in health and income-generating opportunities for local communities.”

For the hundreds of climbers who risk life and limb to summit Everest every year, there is little mood to stop climbing, and there’s no sign that the Nepali authorities – or the Sherpas – want to reduce the numbers either. It doesn’t add up to a happy ending.

Jon Krakauer’s book doesn’t have a happy ending either. The expedition he was part of encountered a vicious storm, which left eight people dead. Krakauer survived, but the events left their mark, and left him questioning his own motives for wanting to reach the summit. As for the then record number of people who died on the mountain in 1996’s climbing season, and the clamour to change, Krakauer wrote this:

“Analysing what went wrong on Everest is a useful enough exercise; it might conceivably prevent some future deaths. But to believe that dissecting the tragic events of 1996 in minute detail might actually reduce the death rate in any meaningful way is wishful thinking. Truth be told, climbing Everest has always been an extraordinarily dangerous undertaking and doubtless will always be, whether the people involved are Himalayan neophytes being pulled up to the peak or world-class mountaineers climbing with their peers.”

Sadly, Krakauer’s analysis, more than 20 years later, is on the mark. More climbers than ever will attempt the summit next year and it’s almost a guarantee that some of them will die. As long as Everest is there, people will want to climb her, and, as George Mallory found out to his cost (he died on his third attempt to make it to the top), believing you can climb Everest and making it back down alive are two very different things.