A couple take a seat on a bench in a bustling city square without exchanging a word or a glance. From a distance, they seem the perfect incarnation of modern society’s technological isolation. On closer look, in fact, not so much – instead of tablets or cell phones, they’re holding sketchbooks. While they observe the surroundings with an attentive eye, vivid sketches quickly fill the pages.

In times when youngsters play on touchscreens from the cradle and everyone carries a camera in their pocket, walking around with a sketchbook and a handful of pencils can look like a nostalgic pastime. However, the urban sketching movement (USk) arose in the digital era, and is very much connected to it. Initiated by Gabriel Campanario (@gabicampanario), a Spanish-born journalist working on the Seattle Times who began to illustrate his pieces instead of conforming to the industry standard of photography, the movement developed from a blog back in 2008. In a well-rounded and successful strategy, Campanario set a date for the blog to air and promoted the initiative beforehand in the press, while simultaneously contacting illustrators from all over the world to contribute sketches. “It was madness, back then. You would post a sketch on the blog, and ten minutes later, you had to scroll and scroll if you wanted to see it,” says João Catarino (@joaocatarino65), a Portuguese illustrator who was among the first to be contacted. From day one, the manifesto was clear: all sketches should be drawn on-site, without previous study, and the movement should be all about sharing in an inclusive and non-judgemental atmosphere.

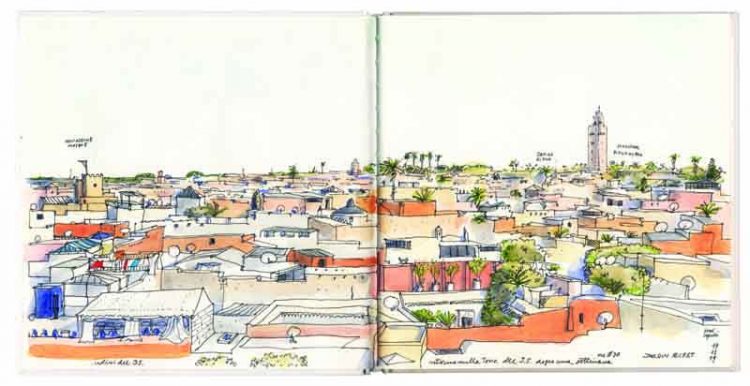

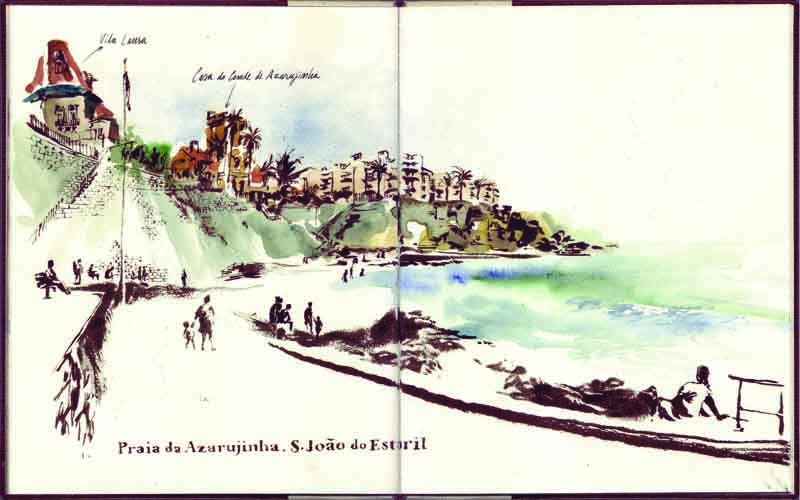

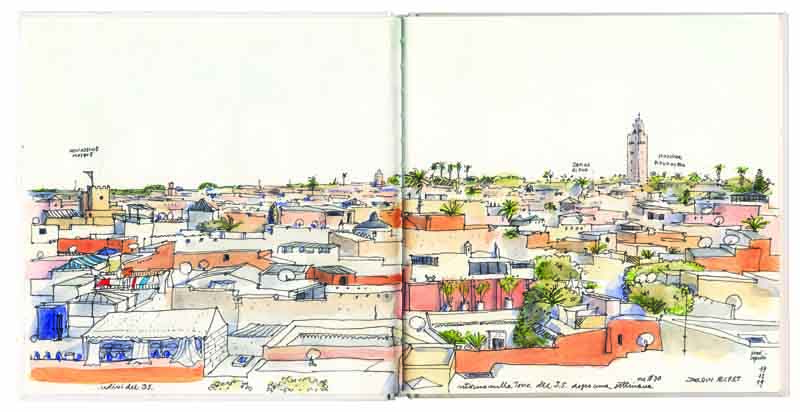

Even though USk is, in essence, analogue, it wouldn’t exist in its current form and international scope without the help of the digital. Since the launch of the international blog, many countries have also created national ones, and due to the swift changes in the internet landscape, a big part of the action has since moved away from the blogs and into social platforms like Facebook and Instagram. “It’s curious how the digital revolution has fostered the movement, because in many senses USk is about experiencing the world without technology,” says Catarino. “In a way, USk is a response to the massification of tourism and the hustle of cameras. There’s this wistfulness associated with old travel diaries, like Delacroix’s Carnet de Voyage au Maroc, that permeates the visual expression of most sketchbooks.” The appeal of the archetypal explorer and adventurer who documented their travels in sketchbooks has had a global influence, and even brands have realised its value. Louis Vuitton was among the pioneers of the trend, inviting illustrators around the world to create branded carnet de voyages about multiple places to be displayed alongside suitcases in shop windows and advertising. On the other hand, Moleskine developed a hyperbolic brand narrative associated with a romanticised link to Picasso, Hemingway and Chatwin’s notebooks, despite the company’s foundation in 1997.

Nineteenth century and earlier travellers didn’t have the option of a camera, though. Besides nostalgia, what’s feeding and filling sketchbooks the world over? “Our times engender a certain passivity; our devices that make things happen in front of our eyes convert us into witnesses. But there’s something enlivening about drawing, and the interaction it establishes with the world around us – it’s curiosity embodied,” says Douglas B. Dowd, Professor of Art & American Culture Studies at the Washington University in St. Louis and author of the book Stick Figures: Drawing as a Human Practice. “Somewhere along the way, we’ve mistaken drawing for a professional skill instead of a human capability. Because drawing is connected to painting (which I think is a mistake), people got to think that the purpose is to reproduce reality, which implicates professional techniques. But in human history, drawing has always been about consolidation and dissemination of knowledge. What makes an insect an insect? How does a machine work? From natural sciences to engineering, all types of disciplines used to be taught through drawing, because the intersection between hand, eye and brain facilitate knowledge, namely through a more profound understanding of proportion and detail. Our brains became larger after our thumbs became opposable; how we use our hands is part of how we learn and engage with the world. If we get rid of the idea of drawing as illusion-making, we are freed of the aesthetical anxiety that seems to universally descend around puberty.”

Perhaps, given the close link between drawing and learning – or, even more, the fact that most of us do suffer from aesthetical anxiety the moment we grab a pencil – the demand and offer of urban sketching workshops rose as the community grew larger. “People who have never drawn are often the easiest to teach: they have no assumptions of things they can and cannot draw, no habits that need to be undone to see and draw better, and they are open to drawing anything,” says Suhita Shirodkar

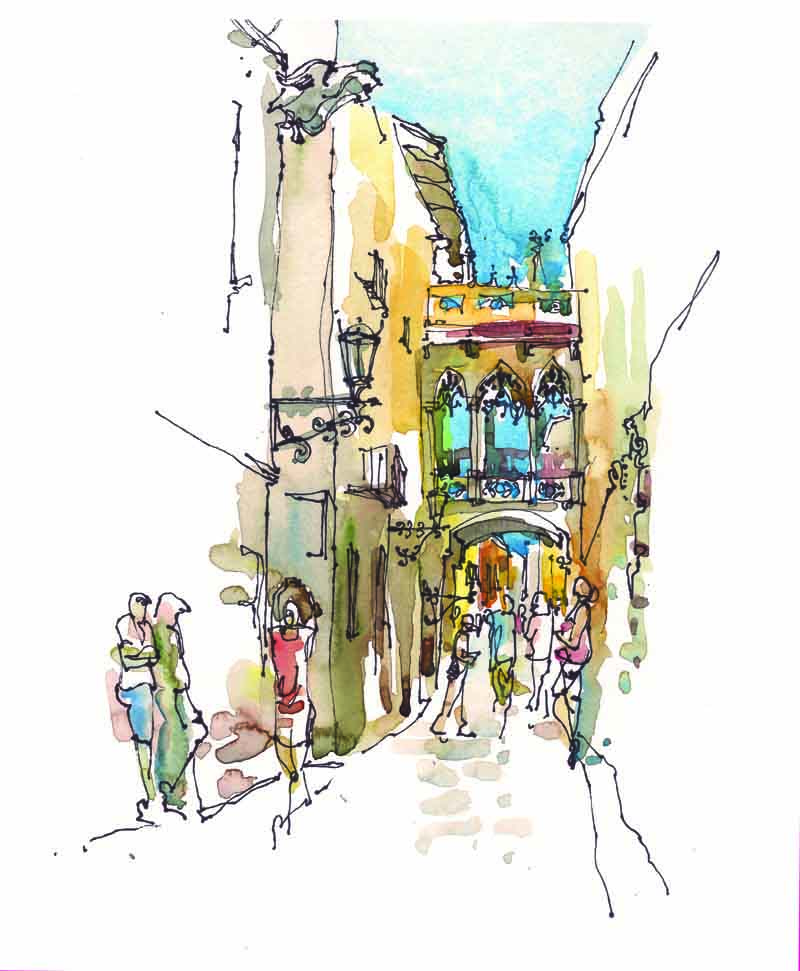

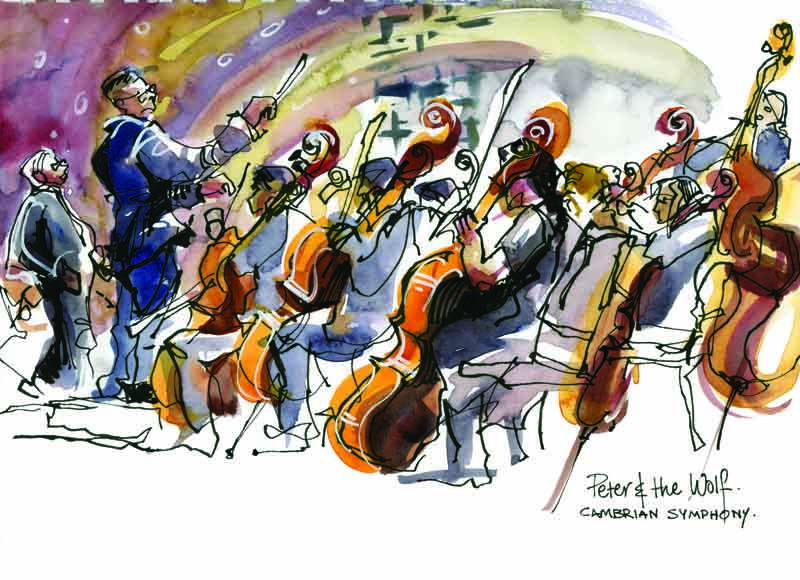

(@suhitasketch), an Indian-born and California-based illustrator. Like many professional illustrators who have also embraced urban sketching, she is an active member of the community and often teaches workshops. “People often come to a workshop to learn how to draw postcard-pretty images, but I like to think that the experience of drawing is more valuable than a particular kind of result. I teach techniques like focusing only on outlines, on a particular colour, on high contrasts, yet the goal is having people looking differently at what’s in front of them, more attentively, more present,” says Catarino. “The beauty of urban sketching is the rawness and immediacy that drawing on location has, and that’s hard to capture in a studio setting. It’s an unfiltered impression that captures the energy and vitality of the place. You can put a bunch of urban sketchers at the same spot and have them draw the same scene, and each one will capture a different aspect of the scene in a different style,” adds Shirodkar.

Workshops aside, gathering to draw – no tutoring or fees attached – is still a pillar of the movement, even if most of the sharing happens online and some of the initial spontaneity has been lost. The Urban Sketching Symposium has been held every year since 2010, and the last edition brought together 1500 attendees to sketch the scenic canals of Amsterdam. Though the community is global, symposiums tend to be expensive and mostly held in Europe and North America, and are therefore less accessible to enthusiasts from the Southern Hemisphere. Naturally, not all countries are equally active, but neither are they equally inclusive, as a glance into several countries’ blogs will tell: some publish all the work submitted, while others appear to do a preselection. Still, the sense of community is most likely the linchpin of the movement’s success; in many ways, it isn’t limited to the interaction between sketchers – drawing on-site attracts people, curiosity, conversation. “While a lens can be intrusive, a sketchbook draws people’s attention, especially children. On my travels to Africa, I often find myself losing sight of the subject when drawing because I’m suddenly completely surrounded by kids and, later, their parents. There’s something about the process that feels like magic, especially in the eyes of children: a sketch reveals itself little by little, a mystery that gains new meanings with every brushstroke. They’re hooked to the page,” says Catarino.

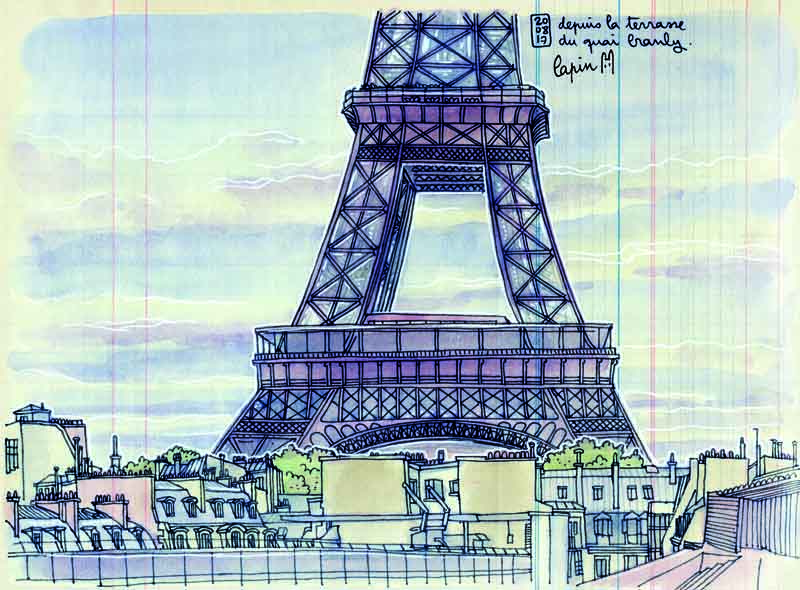

For most sketchers, drawing becomes a way of travelling. “Drawing connects you to a place. To sketch a city, you have to understand it, to look closer to the surroundings to make it your own. You decide which details to convert into strokes, lines, colours, and your memories become fixed on the pages. Now, if I visit a place without sketching it, I feel I haven’t been there at all,” says French illustrator Lapin (@lapinbarcelona). In addition to a strong sense of place, the sketchbooks convey a temporal dimension, as each page is a reflection not only of the surroundings but also of the sketcher’s attitude on a particular day, and the materials they had. The resulting differences and discontinuity evoke a feeling of chronological progression. “A sketchbook used like a diary becomes a private, intimate object, and you fill it with all your precious memories. There’s a certain freedom in keeping mistakes and ‘bad’ pages among the sequence. I think I have filled hundreds of them over the years, and losing one is painful,” says Italian illustrator Simonetta Capecchi (@simo_capecchi).

The concept of travelling has a broad meaning within the USk community, and is intrinsically related to the idea of seizing the moment. Travel can mean anything from an adventure fit for a Delacroixesque carnet de voyage to a simple commute to work; it can be a ten-minute drawing captured in a short routine break leaning against a wall or a two-hour immersion in the landscape. “Urban sketching has profoundly changed how I see the world. I no longer hurry through my daily life and my travels; I go slower and see more deeply. I try to see both the places I travel to and my everyday world with the fresh eyes of a traveller. Everything is fascinating when you stop to look at it carefully and sketch it,” says Shirodkar.

The term “urban sketching” wasn’t coined out of thin air – most of the sketches circulating are indeed urban landscapes. Cities never sleep; there’s no time to waste in the urban jungle. Or maybe, a sketchbook and a pencil is the perfect excuse to slow down the city.