Knoedler & Co. was the oldest commercial art gallery in the US. Established in 1846, it cultivated a reputation as one of the world’s leading dealers of old master paintings, with Andrew Mellon, John Jacob Astor, Cornelius Vanderbilt and J.P. Morgan among its elite group of collectors, frequenting the institution’s New York City storefront to purchase rare and celebrated masterpieces.

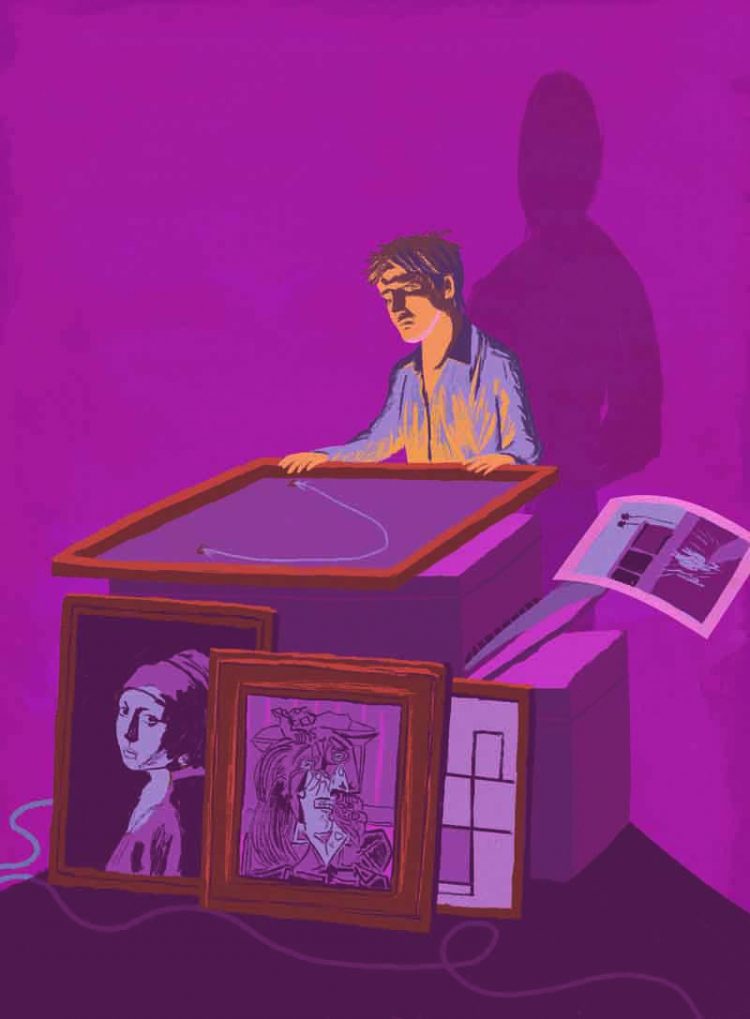

But by 2012, the FBI was investigating dozens of dubious paintings sold by Knoedler over the years: forged works marketed as unknown Jackson Pollocks or Mark Rothkos, among others. When it closed in 2011, amid lawsuits for forgery, both art and finance worlds were abuzz. How did such a storied institution – one that had weathered 165 years of American history and changing tastes – give rise to the greatest art scandal of all time? And how can buyers today keep pace with increasingly sophisticated forgery techniques?

It takes a team of experts, including art historians, lawyers, materials scientists and researchers to authenticate works of art, from prints advertised on eBay to multi-million dollar canvases sold at auction. These professionals perform the most rigorous due diligence to identify fakes and forgeries, protect high stakes bids, and ensure that buyers go home with a bonafide treasure. Their work underscores art fraud’s tremendous financial consequences for both individual buyers and the market as a whole; perhaps more important, it serves to counteract cultural crimes, protect our shared heritage and preserve the art historical record.

The art market is considered one of the largest unregulated industries in the world. Art fraud includes a broad range of crimes, from falsified signatures and forged documentation to shill bids. And the market’s lack of transparency harms amateur and experienced collectors alike: anyone can be a victim of art fraud.

“I’ve worked with billionaire collectors who have unwittingly purchased fakes and forgeries,” says Colette Loll, an expert in art fraud and the founder of Art Fraud Insights, a company based in Washington that investigates the sale of fake art. Even the most sophisticated of buyers, she explains, will overlook red flags in order to secure a piece they believe is exceptional or undervalued.

The factors that drive such a decision are complex, but art fraud always involves what Loll calls a “nugget of plausibility,” which is used to exploit an eager buyer. “Both the believer and the deceiver play an active role in the fraud.” Sales can be further complicated by a triggering event such as death, divorce or inheritance, and buyers may be seduced by a false sense of urgency created by an auction. “Long gone are the days when a single connoisseur could examine a work of art and say it looks right or it doesn’t,” Loll says. “There are some very clever workarounds.”

During several prominent art scandals of the past, for instance, investigations revealed that an art forger had imitated the styles of contemporary masters, then used tea or vacuum cleaner dust to give the knock-offs a time-worn illusion of patina. Dealers who sold them ultimately profited tens of millions of dollars from these counterfeit paintings, banking on this artificial aging process as well as on a keen grasp of the psychology of consumers willing to be fooled. Collectors eager to pay competitive prices for investment pieces must therefore recognise that the complexity and opacity of the art market can also aid fraudsters in avoiding detection.

One concern expressed by Loll is the increasing sophistication in fake art tied to advances in art imaging and analysis tools. Indeed, technologies used to authenticate works of art by identifying the artists’ materials and techniques are now being exploited by clever forgers themselves (such as Wolfgang Beltracchi, who admitted to forging hundreds of paintings in an international scam that netted millions of euros).

This makes for a heightening arms race between the forger and the scientist. While Art Fraud Insights works at the intersection of art, psychology, technology and the law, the company relies on materials science as the first line of defence to authenticate works of art.

“Materials analysis guides us if and when we run into anachronistic materials that wouldn’t have been available at the time,” says Dr Jennifer L. Mass, whose New York-based company Scientific Analysis of Fine Art (SAFA) partners with Art Fraud Insights. Mass uses elemental imaging, molecular analysis tests and microscopic techniques to interrogate works of art, from paintings to porcelain to ancient manuscripts. “Even as forgers become more sophisticated about using period materials,” says Mass, “we see trace elements we wouldn’t expect to see in an authentic work, and we don’t see degradation materials that we would expect to see.” Modern paints, for example, often contain fillers and paint-binding media that simply could not have existed in earlier eras, even if the pigments appear to be period-appropriate.

Scientists like Dr Mass work hand in hand with attorneys who draw up airtight sales contracts, as well as related agreements (on behalf of experts accepting submissions for artwork authentication), investigate catalogue listings and closely monitor market disputes.

“Sophisticated, high-net-worth clients may want to perform the same level of due diligence prior to an artwork purchase that they would undertake for a different investment, such as real estate, but need help navigating what that diligence looks like for this unique asset class,” says Megan Noh, a Co-Chair of the Art Law group at Pryor Cashman LLP, the firm that represented the Hilti Family Trust plaintiff in the Knoedler scandal. “As a legal advisor, I’m in the position of helping assess risk by asking: was the artwork purchased from an auction house? Is it in the relevant catalogue raisonné (a comprehensive listing of all known artworks of an artist)? Was the attribution warranted, and if so, who assumed liability on that issue, and for how long?”

Attorneys in the field also track down connoisseurs (those familiar with the technique, palette and gestural work of the artist in question) and engage art historians to conduct provenance research that may validate an artwork’s history, or provide testimony during trial if a dispute arises. These experts carefully examine consistency with an artist’s oeuvre, considering characteristics that may or may not be in keeping with a master’s general style.

Noh is careful to underscore that these cumulative measures are effective at proving forgery, not establishing authenticity. “Science can prove that something is a fake,” she explains, “but science can only support that something is authentic.” In other words, technology can never guarantee without a shadow of a doubt that a Vermeer is in fact a Vermeer. That determination, it seems, still remains less a science than an art.

ILLUSTRATIONS: Finn Dean