Six years ago on Latin America’s well-trodden hippy trail, I made the classic backpacker pilgrimage to Lake Titicaca on the Peru-Bolivian border. Set in the shadow of the mighty Andes, its drawcard (aside from being the birthplace of the sun in Andean folklore) is a cluster of golden thatched floating homes. Here, islanders in derby-style hats and crayola hooped skirts tour travellers around their aquatic lodgings in ceremonial-looking boats, balsas, maybe selling you a few tasselled woven wares along the way. I remember thinking this was like nothing I’d seen before, but gave little thought as to the extraordinary feats of engineering these island communities were.

On the world’s highest navigable lake, a millenary South American civilisation named Uros, found a solution to living in this seemingly inhospitable place right under their noses: totora grasses. Built originally as a defensive mobile floating city, everything from boats to cooking fuel and medicine continues to be crafted from the buoyant reed-like totora that flourishes in the lake’s marshy shallows.

Days earlier I was trekking to Machu Picchu, built of course by the indefatigable Incas – innovators in agriculture as well as hydraulic engineering, who rendered arable land in the hilliest of terrains. The Uros pre-date Incan civilisation, and yet these living examples are more than often romanticised by travellers (myself included), or labelled as primitive versus innovative.

It is a mindset that Australian-born author, academic, activist and designer Julia Watson is seeking to challenge and re-frame with her book, Lo–TEK Design by Radical Indigenism. “We have this view that if you are indigenous then you’re primitive and the ways that you live are primitive,” she says.

Bound in Switzerland, the tome – beautiful in its own right – represents two decades of travelling to the farthest reaches of the globe in search of unsung nature-based technologies, masterminded by indigenous communities.

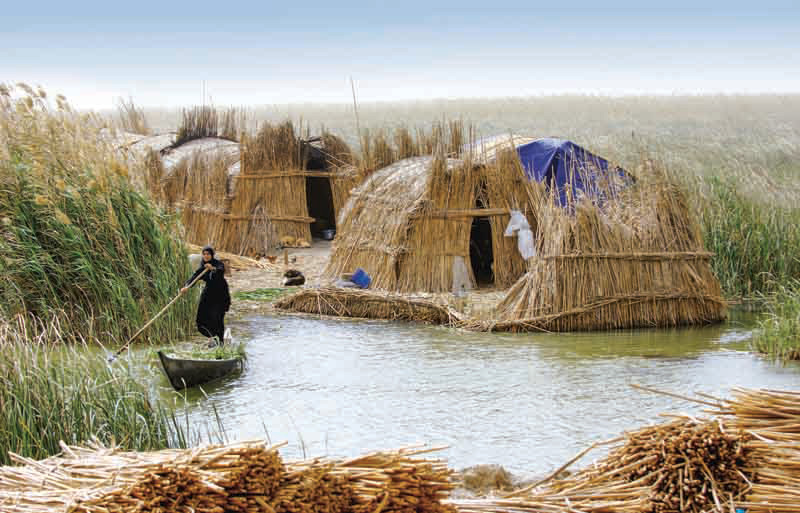

Many are remarkable feats of physics and ingenuity, which rely on a reverence for nature and knowledge that transcends generations. Take, for example, the indigenous Ifugao people who carve rice terraces out of sheer mountain hillside, or the elaborate floating basket homes of Ma’dan living in Southern Iraq. Constructed without nails, glass or wood, they have existed for 6,500 years.

“There were tons of floating islands that were being built in China and Europe 500 years ago but we don’t have them any more,” says Watson. “It’ll stop if we don’t document it.”

Watson’s book, published by Taschen, celebrates some 120 living examples across 20 countries, from Peru to the Philippines, India to Iran. It also encompasses most living ecosystems, from forests and mountains to wetlands and deserts. Rather than taking readers on an anthropological journey, Watson interprets these concepts of indigenous design through an architectural lens. The 42-year-old teaches Urban Design at Harvard and Columbia University and is the Director and Co-Founder of A Future Studio – described as a ‘collective of conscious designers with an ethos towards global ecological change’. Their shared mission is to find Lo-TEK (a term coined by Watson, meaning traditional ecological knowledge) technology solutions, underscored by nature and sustainability.

Growing up in a progressive suburb in a conservative Australian town, the author’s own “aha” moment happened in the dusty shelves of Brisbane’s University Library, aged 18. “It was like someone just lifted a veil,” she says of reading colonists’ first-hand accounts with indigenous peoples when travelling across the desert during the 1800s. Her long-time fascination with sacred and cultural landscapes was seeded.

One sacred place that caught her attention was Bali and its thousand-year-old agrarian system, known as subak, itself steeped in ritualism. Also a complex social system that’s managed by the island’s indigenous leaders, the water that flows from channel to rice paddies (using gravity, rather than fossil fuels), is regarded as a gift from the goddess of its volcanic crater lakes. The island’s 50,000 acres of terraces have been farmed this way since the 9th century, but will depend on the harmony between man and nature to continue into the next one. Despite being inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2012, this sophisticated irrigation system is increasingly stressed by hotels and resorts excessively pumping groundwater.

“These technologies are not only undervalued by the West, they’re undervalued in the places that they exist,” adds Watson. “We talk about biodiversity as what will be the 21st century’s greatest loss. But I think what the greatest loss will be is all the technologies that we don’t even acknowledge as technology yet. That’s the technology that actually captures and provides habitat for all that biodiversity.”

In Iran, underground aqueducts called qanat, which look like giant anthills from the sky, are a time-honoured method for harnessing mountain groundwater, dating back 3,000-odd years. An innovative solution to sourcing pure water in an unforgiving landscape, it’s paradoxical that the country should now be declared a water-bankrupt nation, owing to years of corrupt water management, drying lakes, soil erosion and abuse of the country’s aquifers.

But there are shining examples of where a close kinship with nature reaps economic rewards. Doing their bit to shrink the world’s agro-ecological footprint are the Chaga people of Tanzania, who plant sun-shy coffee plants in the shade of banana trees on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, where biodiversity thrives. “They have a forest food system that’s the size of Los Angeles,” says Watson.

“They’re the most educated and wealthiest tribe in that region of Africa.”

Another sustainable food production model profiled in the book, this time implemented in an urban setting, is Kolkata’s wastewater-fed aquaculture system, crowned the world’s largest. Known as the “the kidneys of the city”, it filters 700 million litres of raw sewage every day, employs 50,000 fish traders and cultivators and provisions the city’s markets with half their green veg quota. “We think of renewable energy in a certain frame, mostly hi-tech, at this moment in time. This particular system doesn’t use energy or chemicals. What it uses is fish, bacteria and algae. The renewable energy in that system is a chemical reaction and species symbiosis that’s completely free and produces economically,” explains Watson.

So successful is the design, which also acts as a natural flood barrier for the low-lying city (and saves Kolkata US$80 million a year), it is now being replicated by other Indian cities like Chennai and Nagpur.

Yielding multiple co-benefits like food and carbon sequestration is a hallmark of these overlooked indigenous design technologies. In north-eastern India, 1,000km to the north of the Bangladeshi border is Meghalaya’s Khasi Hills region – where the indigenous Khasi people navigate swollen rivers in one of the wettest places on earth. Knotted aerial roots are twisted and ‘trained’ into living ladders that straddle gorges and 75-metre walkways capable of supporting up to 50 or more people at a time. Proving their sophistication in developing a symbiosis with mother nature, these stunning structures (that take one generation to build), can also withstand monsoon rains and mop up carbon.

With urban landscapes increasin-

gly vulnerable to floods, unpredictable weather patterns and runaway air pollution, now, more than ever, the world needs outside-the-box design thinking. Solutions to an ongoing climate crisis may not necessarily be rooted in new technologies though. There are lessons to be learnt from the complex ecological relationships indigenous communities have nurtured over millennia. Referring to the case studies in her book, Watson remarks, “Some of the top designers that I work and teach with say, ‘how do we understand how these systems work? They are so advanced.’”

Take, for example, Rotterdam – which aims to become a sustainable design capital, and a solar-powered floating city. What can it learn from the Uros and Ma’dan?

“These islands are floating and buoyant because of multiple types of decomposition,” Watson says of the Uros communities. “There’s talk about using electrified biorock as a device for new, floating cities. Use of those electro magnetic fields, which keep the rocks afloat, disrupts all the electro magnetic fields of apex predators and all the sea creatures that use them for navigation,” argues Watson.

In a world where we’re racing towards the future, maybe it’s time to draw breath and observe the inherently sustainable and time-tested practices of the past, which, by all accounts, seem to be holding up rather well.