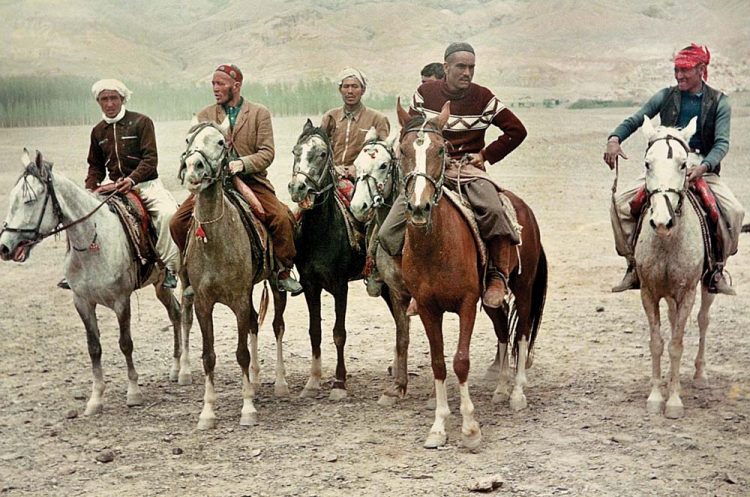

It was, at one point in time, a rite of passage: a journey that started in Western Europe and crossed through the Balkans, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. This was a trek that saw tens of thousands of young people attempt to find enlightenment, inner peace, or just a rollicking good time. These were the hippies, the overlanders; young men and women who wanted to understand the world and their place in it.

While the tourism revolution in the 1960s saw the majority of travellers head to the beaches of southern Europe, a different breed of tourist had other plans. They would traverse Europe, the Middle East and Asia, spending months travelling across 11,000 miles of terrain in order to find whatever it was they sought. Some yearned to escape the drudgery of their dead-end jobs in Luton or Liverpool or London, heading to Varanasi in India, and Kabul, and Kathmandu, and to Thailand’s then-unspoiled beaches.

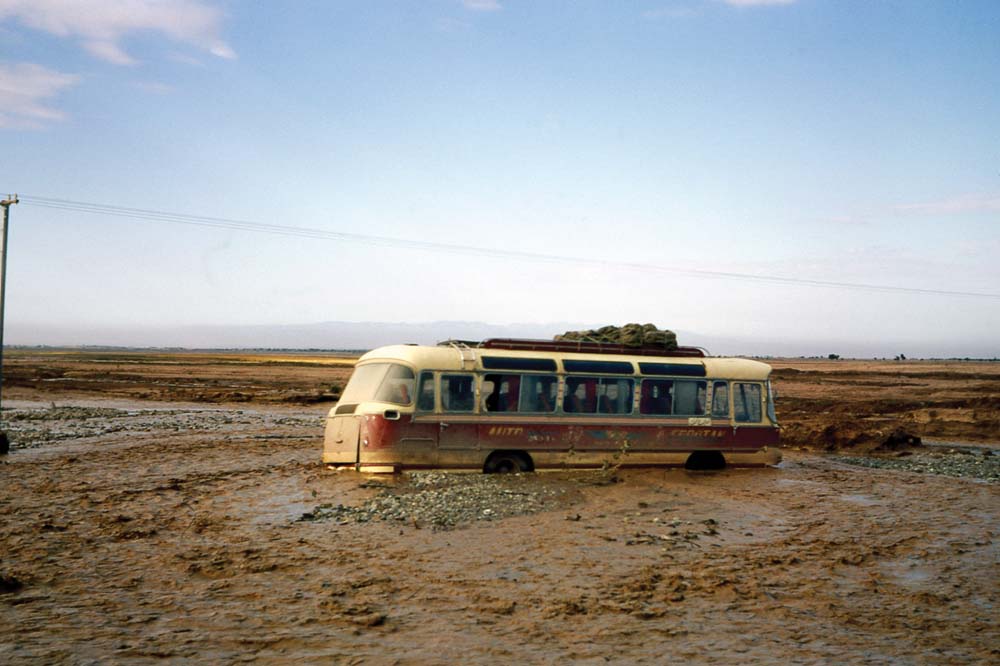

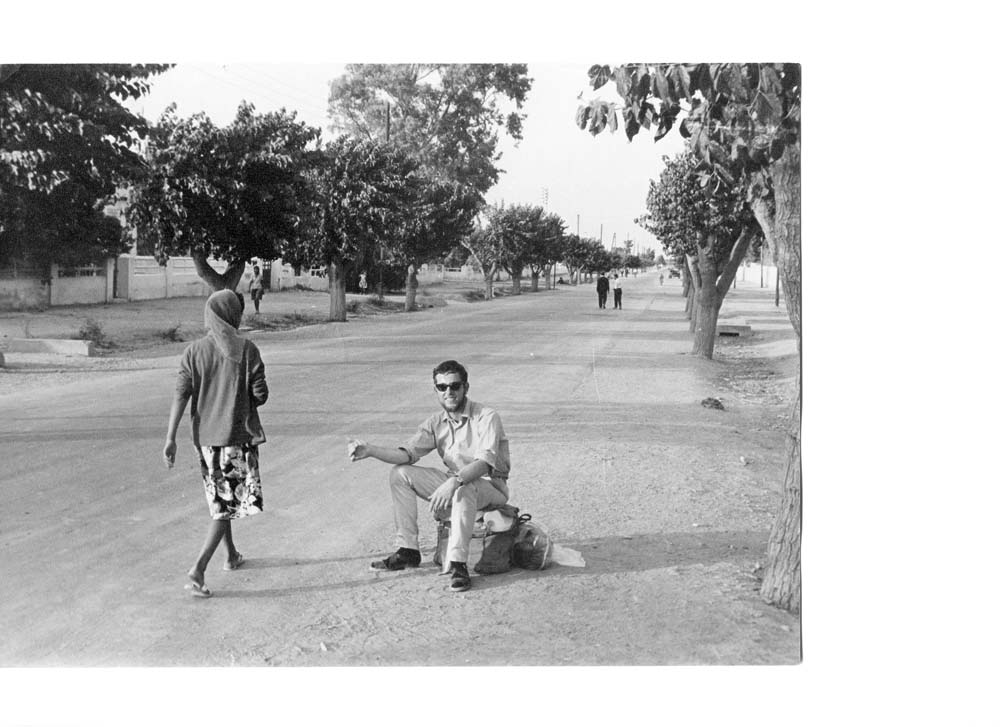

In some ways they were following in the footsteps of the beatniks: men and women who travelled through America, Jack Kerouac’s On The Road clutched in their hands and an ideal of escaping from the conformity of the post-World War II America. The journey was slow – planes were out, and the majority went by bus or by train, or by hitching lifts. One company to capitalise on the trend was aptly-named The Magic Bus, which picked up travellers in small, private buses in Amsterdam. Prices were cheap – in 1971, a journey from Istanbul to Kathmandu cost just US$15.

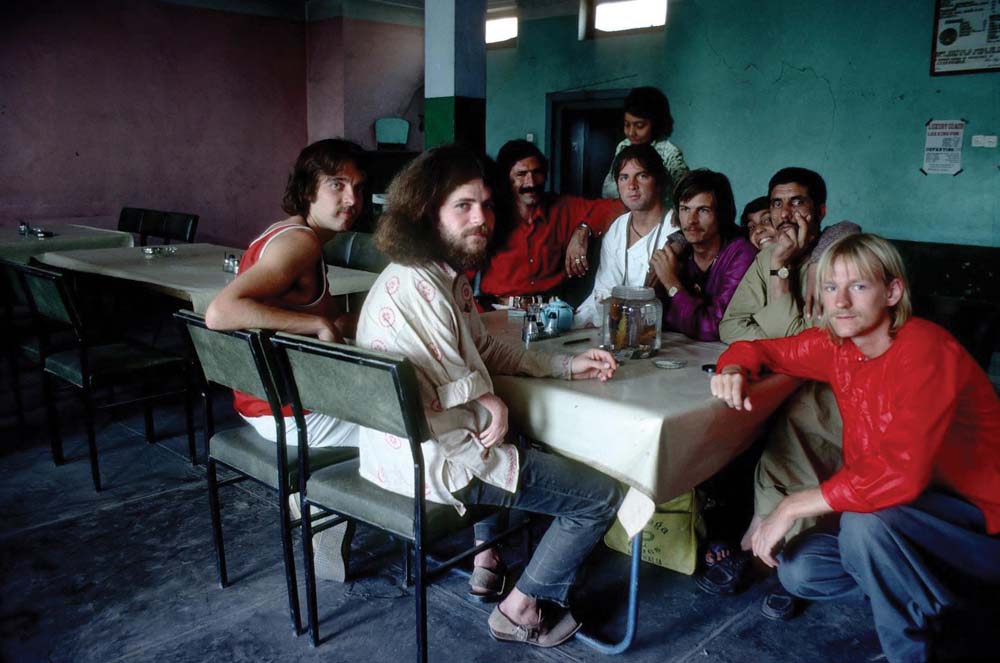

They clutched the BIT Guide, a prototype travel guide that was really just photocopied sheets of paper stuck together, filled with information on bus prices, clean guesthouses and the best place to get breakfast in Kabul. The stops along the way became intertwined with 1960s counterculture: Paradise Beach in Mykonos, Chicken Street in Kabul, Freak Street in Kathmandu, The Pudding Shop in Istanbul. These were the original social networks: legions of travellers exchanging currencies, swapping stories, giving advice and updates from the road.

“I was eighteen years old when I went,” says Richard Gregory, who made the trip in 1974. “A basic ticket cost £50 from London to Delhi, much cheaper than flying, and it took two or three weeks. I was away for four months in total, coming back on local public transport as far as Istanbul then hitchhiking across Europe.”

In Goa, long a hotbed of alternative culture, many travellers stayed – some joining ashrams to attempt to disco-

ver themselves within another culture. “People headed south for the beaches of Goa in winter, based around the village of Anjuna, where there were no other tourists,” says Gregory.

Others headed further west, towards Kathmandu, which became the city most associated with the route. “To the road-sore travellers, medieval Kathmandu was a kind of promised land, a paradise lost and rediscovered,” says Rory Maclean. In his seminal book on the trail, The Magic Bus, he wrote: “The travellers checked into the Hotchpotch and the Matchbox, dirty warrens of cell-like rooms with low, head-cracking doorways and debated how best to heal the world and their back.

“At the Bakery, many of them sold their jeans for strings of amber and red felt boots embroidered with flowers. Back then, Kathmandu was a place where many believed they could find a new way of living, where they had a chance to imagine a world without boundaries.”

The overland route was nothing new, of course – the Silk Road was an important economic and cultural route for centuries, before the the isolationism of the Ming Dynasty shut it down. That so many of the stops along the hippie trail were isolated from Westerners nearly 400 years later, reflects the finality of the Ming Dynasty’s decision. Kathmandu, for example, was completely unequipped to deal with an influx of Westerners; the first group of official tourists only arrived in the country in the spring of 1955 and were greeted by King Mahendra himself. The tourists – all Americans – were part of a round-the-world cruise and spent two days in the country on a stage managed visit.

Further east of Kathmandu the trail ended, blocked by the Himalayas. Some flew to Indonesia or Thailand and then onto Australia, where they attempted to integrate back into Western life. Others stayed on as long as they could, until they either ran out of money, or went slightly mad. Others still had a more tragic ending, their sense of purpose evaporating as they reached the end of the line. As Rory Maclean wrote in his book, The Magic Bus: “Many intrepids reached Nepal and found themselves at a loss. Was the sacred mountain landscape really their spiritual haven? Could isolated Nepal actually sustain a harmonious fusion of East and West? And if Kathmandu, hidden by a ring of snow-covered peaks, wasn’t paradise, then where was it? No one had asked where to go after the End of the Road.”

During the 1960s, Nepal had opened itself up to tourists, but the tourists that came were not the middle-aged tour groups that so impressed the king back in 1955. They were young, dreadlocked dreamers, many of whom had no intention of leaving. By the mid-Seventies any idealistic view the Nepalis had about tourists had long since vanished. King Mahendra died in 1972, and in 1975, a few months before his son, King Birendra’s coronation, there was a mass clear out of foreigners. The hippies had outstayed their welcome and had turned the area south of Durbar Square in the centre of the city into a mess. This was the end of Freak Street and a precursor of things to come.

Pressure came from the West too. In 1973, some Western governments forced the Nepali government to revoke long-term tourist visas, sick of seeing their citizens return home with fried brains. The same year, Kathmandu’s Chief of Police started demanding a monthly $1,000-rupee bribe to extend a visa. But soon, paying a bribe would be the least of the overlanders’ worries.

In 1979 Russia invaded Afghanistan, and the country was effectively closed off to Westerners. Later that year, Iran had its revolution and that country too was no longer welcoming to tourists. Little by little the route had become more dangerous, and there were few willing to attempt it. Some did of course, and some died trying. Most others went home or kept going west, ending up in Australia or New Zealand. By the early 1980s, any hopes of a ‘hippie revolution’ had long since died. Neo liberalism economics had taken over the US and the UK and global capitalism had begun to dominate. Idealistic notions of ‘peace, love and happiness’ seemed like what they were: a throwback from another era.

Some even blamed the hippies for the seismic shifts in geopolitics. The legendary travel writer Bruce Chatwin, once said that Afghanistan’s descent into chaos began with the peace-loving hippies who descended on the conservative country, driving “educated Afghans into the arms of the Marxists.”

For some, the whole notion of Eastern Enlightenment smacked of ignorance to begin with. Even now, forty years after the end of the trail, those clichés die hard. As the Nepali writer, Rabi Thapa writes: “As recently as 2000, the Let’s Go guide declared that “every romantic ideal you have ever envisaged about the Himalayan Kingdom is fulfilled.” Let’s get this straight, this ain’t no Shangri-La man, it never was. Most Nepalis are poor, some are rich, but we’re all so disenchanted with our Oriental enchantment that we are leaving in droves to nurture our private Nepals of the mind, an irony lost on most visitors. Where are we going, you might ask? Well, we have our dreams too – the siren song of the West is irresistible. Maybe if we meet in the middle, we’ll exchange notes.”

Yes, globalisation has ensured that the hippie trail is now just a snapshot of a time before true mass air travel, before the internet, before the sameness that permeates so many places. The stops on the trail were – to Western eyes at least – truly eye opening experiences, experiences that changed the lives of many who travelled the route, as well as those that they met. If some of the ideas spouted by the hippies now sound rather naïve, it’s at least hopeful, and hope is a commodity in short supply in places such as Kabul, Peshawar and Kathmandu these days.

“For me, the trail was life-changing in terms of education and personal development,” says Gregory. “I came home with a much better understanding of the world and its people, and a lot more confidence in my own capabilities. Those of us who did the trip are not getting any younger, and the trail will soon become a minor footnote in history at best. There have been attempts to “recreate” it for modern times, but without a peaceful Afghanistan the idea is a non-starter. And – there are very few hippies left.”

Five stops on the trail

1. Istanbul

As a trading hub for centuries, Istanbul has always been cosmopolitan. The locals barely blinked an eye when wide-eyed, tie-died hippies started arriving in the 60s. But the places where the overlanders made their home – the Pudding Shop, for example – have long gone.

2. Peshawar

This chaotic frontier town has always attracted the more adventurous traveller, at least until the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, when Peshawar became a staging post for Mujahedeen groups. Back in the 60s, it was more welcoming to foreigners, who would crash in flop houses and haggle with stallholders.

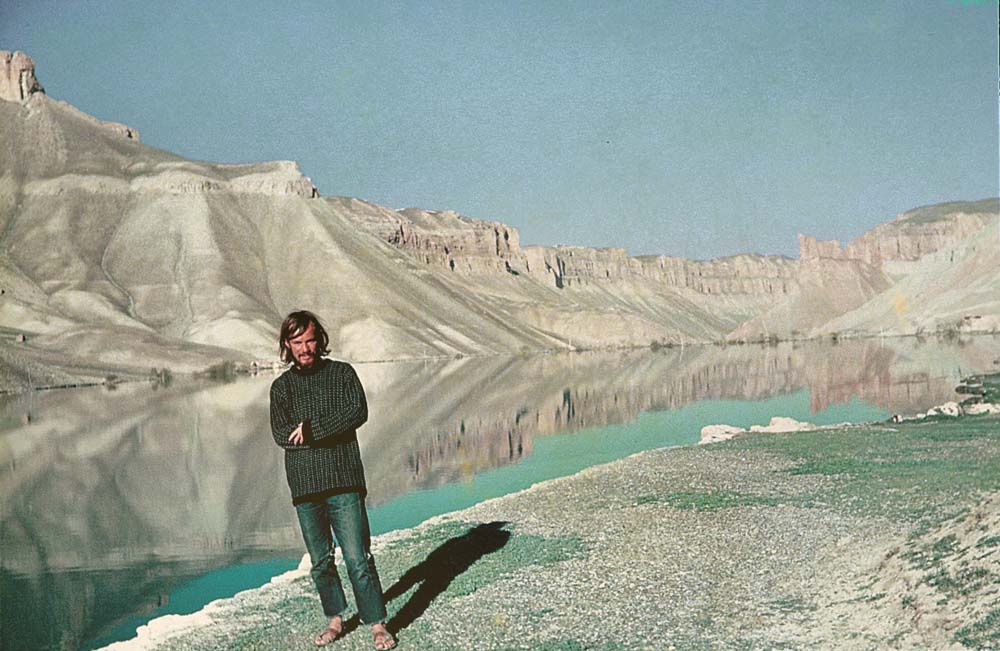

3. Bamiyan

Long fabled among travellers for majestic buddhas that dominated the valley, Bamiyan attracted hordes of travellers for its climate and incredibly friendly locals. The tragedy of Afghan’s more recent history is that a place that was one of the route’s highlights became inaccessible to all but the most intrepid.

4. Goa

Long a magnet for those looking to drop out, this former Portuguese colony was a popular place to take a break for a few months. There’s still a counterculture vibe today, even if five-star hotels outnumber the meditation retreats.

5. Kathmandu

Head to Freak Street today, once with the highest concentration of hippies on the entire trail, and you’ll see few reminders of that golden era – tie-dye sarongs have been replaced by Gore-tex clad tourists planning trips to Base Camp.