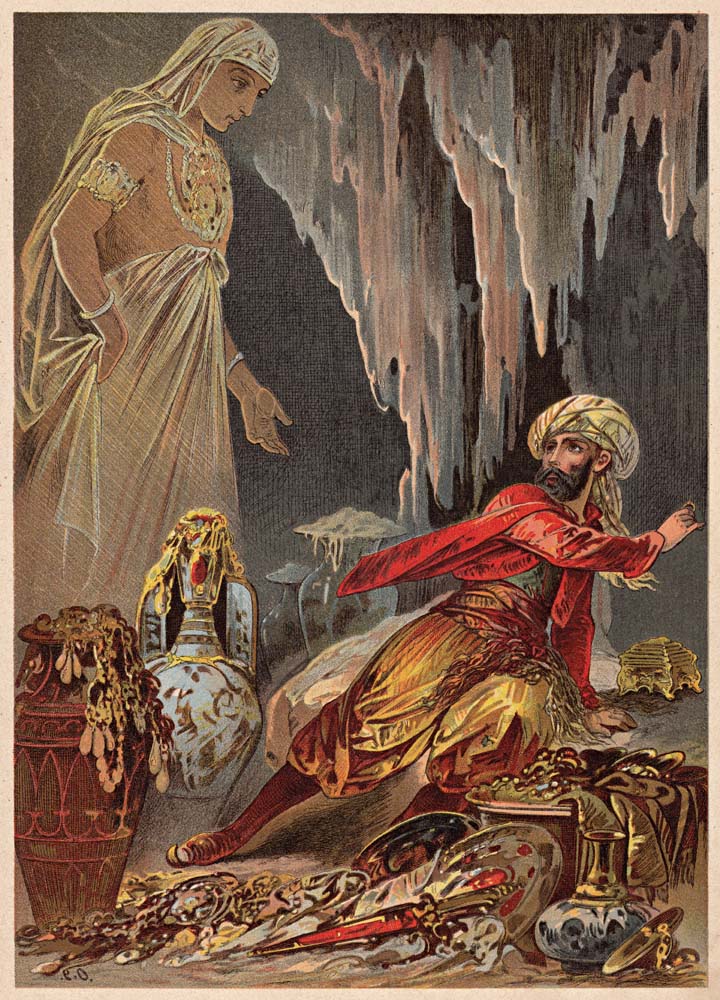

With Will Smith lending his Fresh Prince stylings to the genie, Guy Ritchie’s live-action remake of Aladdin is likely to be one of 2019’s hit movies. After all, the much-loved animated film starring Robin Williams was huge in the early 90s, the music alone leading to a Broadway adaptation. But should we be concerned about an exuberant Californian quipping his way through the Disneyfication of the most famous of all Middle Eastern stories? Surprisingly, one of the pre-eminent experts on One Thousand and One Nights doesn’t think so.

“We’re going to have this barrage of people pointing out how this new Aladdin film doesn’t reflect the modern Middle East,” jokes Paolo Lemos Horta, who recently edited Aladdin: A New Translation. “But if you look at the original story, I’m not sure reflecting the Middle East was ever the point. The tale was probably Persian, yet borrowed from Indian storytelling. The Aladdin story we know today is a combination of a Syrian man telling his tale to a French writer. So there is something wonderfully global and cross-cultural about the way the Arabian Nights stories came about, even in Arabic – in a way, the less you know about Aladdin, the more offended you might be by this film.”

And Paolo Lemos Horta knows a lot about Aladdin. In 2017, he wrote the fascinating Marvellous Thieves, which explored the true origins of the Arabian Nights as made famous by the French and English translations of the 18th and 19th centuries. It celebrated the story of a man from Aleppo, Hanna Diyab, who came into the orbit of Antoine Galland, the ‘author’ of Les Mille Et Une Nuits. Up until recently, it had been suggested that Aladdin was just the figment of Galland’s orientalist imagination; the reality was something a lot more interesting.

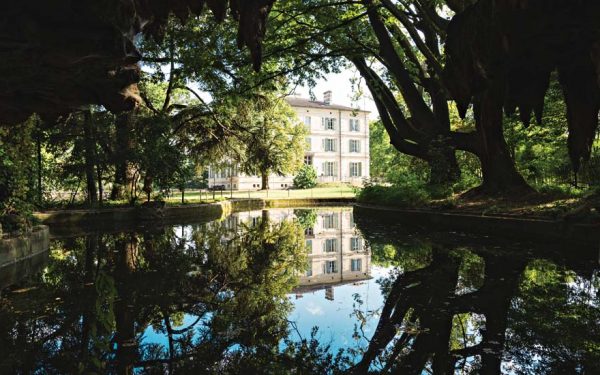

“The parallels between Diyab’s memory of Versailles and the wording in Aladdin are so close one really has to think that some of his wonder at Versailles rubbed off on the story he gave to Galland,” he says. “Of course, it’s very difficult to reconstitute exactly what happened between Diyab and Galland. But what we can say was that the story was the product of both Aleppo and Paris, and Aleppo had Jews, Muslims, Christians and merchants going to coffee shops and listening to stories that had travelled from Asia and Europe. If we think of the story in that way it knocks away at the idea of Aladdin needing to have cultural purity or authenticity.”

]

]

Still, it’s a long way from 18th Century Versailles to the cultural behemoth that is Aladdin today. Why does Horta think it continues to strike such a chord?

“Well, to start with, it’s not just about escapism and genies,” he points out. “It’s about an ordinary boy making something of himself; yes, it’s one of the most widely circulated fairytales in the world, but it’s about someone coming of age, learning a trade, falling in love, going on a quest. He’s betrayed by a father figure. It’s elemental stuff, a global franchise long before Disney got hold of it.”

For Horta, if the Will Smith film means that people come back to Aladdin: A New Translation, so much the better. He’s particularly pleased that the translation by Yasmin Seale – aptly, a French-Syrian herself – has teased out the strong female voices in the original text, which feels particularly apt in 2019.

“It’s exciting to be in the orbit of Aladdin this year,” he agrees. “It’s a moment in time where we need a bit more curiosity about stories that are from more than one place. We need the Hanna Diyab of today, really, rather than being sectarian and nationalistic with literature.”