The Road to Oxiana – what many consider the greatest travel book ever written – starts as it goes on: its author, Robert Byron, going against the grain. He’s in Venice, and instead of waxing lyrical about the city’s architecture or otherworldly beauty, he focuses on some bathers who have gathered in the Lido and “the water like hot saliva, the cigar ends floating into one’s mouth, and the shoals of jellyfish.” It’s typical Byron: funny, acerbic and surprising.

Every story needs a protagonist who is put under pressure, and this one is filled with episodes where Byron attempts – and fails – to rise above his surroundings. Indeed, the whole book is a contrast between the glories of the architecture he sees, the less-than-glorious realities of the hotels he stays in, and the petty bureaucracy he encounters. As a writer, he pulls no punches; there’s no sentiment for the grim lives many of those he encounters have lived, a testament of Byron’s own rather gilded upbringing. Born in London in 1905, he was educated in Eton and Oxford, from which he was expelled, apparently for his “hedonistic and rebellious manner.”

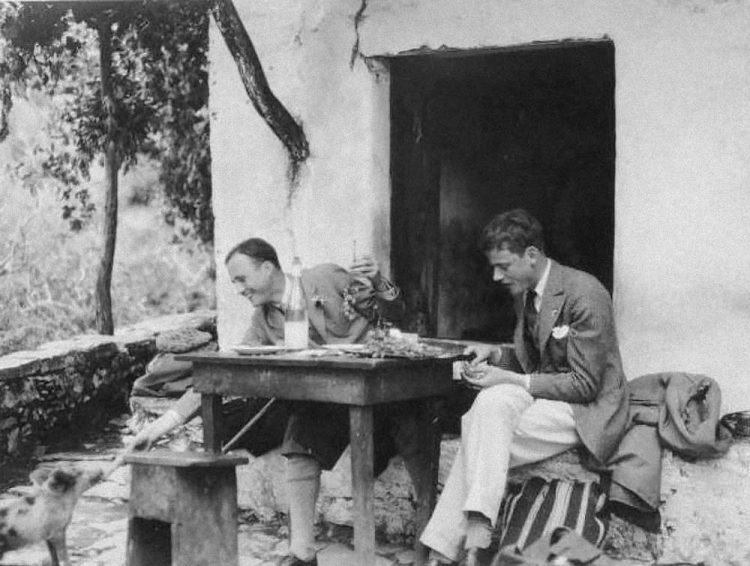

The book is a travelogue, chronicling the journey Byron and his friend Christopher Sykes took to Persia and Afghanistan, passing through Jerusalem, Baghdad and Damascus on the way. Byron’s goal was to discover the origins of Islamic architecture, and their 11-month journey is beautifully rendered; indeed, in many ways, the book has hardly dated at all. Paul Fussell, in his renowned study of literary travel writing between the wars (called Abroad), described Byron’s book as “what Ulysses is to the novel between the wars, and The Waste Land is to poetry, The Road to Oxiana is to the travel book.”

In Jerusalem, Byron begins to engage in his love of aphorisms: “The King David Hotel is the only good hotel in Asia this side of Shanghai.” While these sorts of statements resonate, they are also probably wrong, something some of the book’s critics have pointed out. Indeed, Byron – coming from a privileged background – has the air of a colonial on tour, travelling for the scenery and the architecture, but hampered by the supposed incompetence of the locals.

At one point in his journey, stuck in Tehran, he decided the quickest way to Afghanistan would be to buy a car. He chronicles the Byzantium hell that process entails brilliantly, a four-day process that sees him shuffling between various government departments until finally he manages to purchase a Morris Minor (for £30). His joy is short-lived, however, as we find out in the next chapter: “The back axle has broken, sixty miles from Teheran. ‘To Khorasan! To Khorasan!’ shouted the policeman at the city gate. I felt a wonderful exhilaration as we chugged through the Elburz defiles. Up or down, the engine was always in bottom gear; only this could save us from being precipitated, backwards or forwards as the case might be, over the last or next hairpin bend. Seven chanting peasants pushed the car uphill to a shed in this village. It is a total loss. But I won’t go back to Teheran.”

Indeed, Byron has spectacularly bad luck with cars and trucks and motorised vehicles in general. The car taking him from Beirut to Damascus breaks down soon after departing, forcing the author to take the bus. As he writes at Nishapur, in a remote area of North-East Iran: “One can become a connoisseur of anything. Never in all Persia was there such a lorry as I caught at Damghan: a brand new Reo Speed Wagon, on its maiden voyage, capable of thirty-five miles an hour on the flat, with double wheels, ever-cool radiator and lights in the driver’s cabin.”

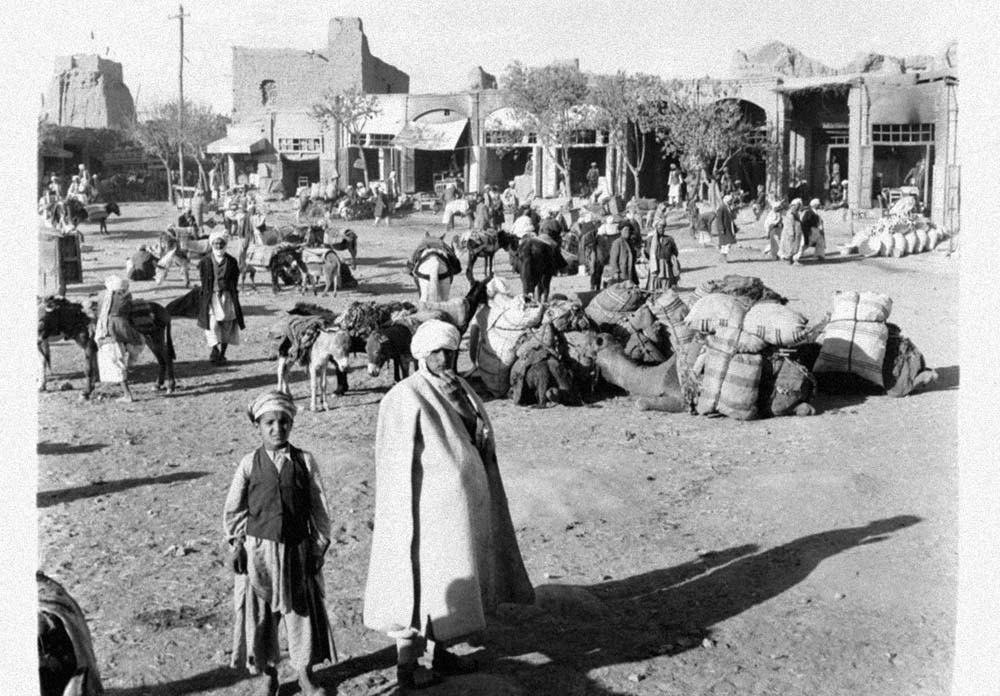

Although Byron’s air of entitlement may permeate his writing, there’s no denying the risks he takes in his travels. The journey between Herat and Mazar-i-Sharif in Northern Afghanistan was more dangerous back then than it is now. Afghanistan, of course, is as far as Byron got. Yet the country is utterly fascinating, and Byron gets up to all sorts of mischief during his stay: he’s arrested, he’s the guest at high society balls, and, unsurprisingly, almost every mode of transport he takes breaks down. He clearly loves Afghanistan, more than anywhere else he visits. At one point he writes about the country: “At last, Asia without the inferiority complex.”

The mid part of the 1930s was a time of real shift in the region; the era of emperors and colonialism was ending, while the era of global oil and nationalism was just beginning. At Rutbah in northern Iraq, Byron notes the changes he noticed since he visited six years previously, the area now filled with pipelines and oil workers. It was a region still dotted with English clubs, with society balls filled with well-to-do Englishmen as well as the local elite. It was the last gasp of an empire, albeit one that Byron doesn’t examine in great detail.

Indeed his interest in politics is largely reserved for the petty: who killed who, who spied on who, who wants who dead. To be fair, that accurately represents the attitudes of the local leaders who he meets, all of whom seem caught up in cheerful paranoia. And it was impossible for Byron – or anyone else – to foresee the sweeping changes that would overcome the region in the following two decades. Large parts of the book are spent chronicling the incompetence of the various border officials he encounters. To take just one example, after he crosses the Iraq-Iran border, he writes: “The Persian officials offered us their sympathy in this disgusting business of customs and kept us three hours. When I paid duty on some films and medicines, they took the money with eyes averted, as a duchess collects for charity.”

There is an air of wistfulness about some of the writing. Byron is very much aware that the “modern world” is arriving in this part of the world, not something he is entirely happy about. “In the old days you arrived by horse,” he writes after visiting the great ruins of Persepolis in South-Eastern Iran. “You rode up the steps of the platform. You made a camp there while the columns and winged beasts kept their solitude beneath the stars and not a sound or movement disturbed the empty moonlit plain. You thought of Darius and Xerxes and Alexander. You were alone with the ancient world. You saw Asia as the Greeks saw it, and you felt their magic breath stretching out towards China itself.”

Byron’s strength is his prose: it’s remarkable in terms of its clarity and ability to evoke a sense of place. He seems able to construct the most unexpected sentences to describe a valley, or the way the light bounces off the walls at a religious site. He never deals in clichés – the bane of many travel books – and his writing is only matched by his powers of observation. He was a sharp reader of people, albeit one unable to suffer fools – witness his hilarious, rather cruel account of a well-off American named Farquharson, who he briefly considers travelling with from Tehran to Afghanistan: “I beheld an unattractive countenance, prognathous yet weedy, with hair growing to a point on the bridge of the nose. From the mouth issued a whining monotone.” Byron, unsurprisingly, made the trip alone.

For all Byron’s adventurous spirit, large parts of his journey are spent ticking off boxes. He must go to Shiraz or Herat or Persepolis – indeed a whole chunk of the trip seems to be spent completing his bucket list, or mired in some catastrophe of his (or some ineffectual bureaucrat’s) making. Byron’s writing is a world away from much of the modern travel genre, awash as it is in hyperbole and breathless prose. In this brave new world of travel writing, views are always “breathtaking,” the locals are always “friendly” and travel is what we do when we want to “find ourselves.”

Yet, some critics have pointed out that for all Byron’s musings on say, Islamic architecture, he actually doesn’t know that much about it. One writer puts this down to Byron’s Eton and Oxford education, which equipped him with the confidence to wax lyrical on anything and everything. The Road to Oxiana wasn’t Byron’s first travel book; he wrote The Station at 22, after travelling with friends to Mt. Athos in Greece, then The Byzantine Achievement in 1929, followed by The Birth of Western Painting the following year. In 1933, First Russia, Then Tibet was published, establishing the author as an important new voice. That tome chronicles Byron’s travels through Russia, a country where he explores the Byzantine origins of Russian iconography. The second half of the book – in Tibet – is where the real treasures are, a valuable insight into a country before it became part of China. While many of his contemporaries acknowledged Byron’s talent, he wasn’t universally liked. The great writer Evelyn Waugh had this to say about Byron: “It is not yet the time to say so but I greatly disliked Robert in his last years, and think he was a dangerous lunatic better off dead.”

Byron finally returned home to England in July of 1934, deflated and underwhelmed to be back. His home country looked “drab and ugly from the train,” and he writes that he is “dazed at the prospect of coming to a stop, at the impending collision between 11 months’ momentum and the immobility of a beloved home.” It’s a feeling familiar to many travellers; as the possibilities of the road recede, the realities of life at home loom large.

Bruce Chatwin, in the introduction to the 1981 re-issue of the book, describes Byron as a “gentleman, a scholar and an aesthete.” While some of the people Byron encountered on the road may have bristled at the first descriptor, there’s no doubt his acerbic, slightly entitled air made him a much more interesting writer than the vast majority of mundane cultural relativists who ply their trade today.

Byron’s life was cut short in 1941, when, aged 35, the ship he was on was torpedoed by a German U-boat. Although we missed out on tales of his future escapades – and inevitable complaints – the world is left with his most momentous work. Imperfect it may be, but in that way still reflects our travels: messy, sometimes unfulfilling, but always worth the journey.