When Oliver Twist arrived in London, his vision was clouded by dark smoke billowing from sky-high chimneys. Fast-forward nearly two centuries and it is safe to say that the Dickensian hero wouldn’t believe his eyes if he fell down the chimney of a current-day, London factory conversion – to find anything but the scenario he would expect.

If grim Dickensian images of assembly lines are still predictable inside industrial buildings in many places, London and most post-industrial cities present a very different interpretation. As the economy shifted from production-centred to the digital, information age we live in, factories moved away from the city centres and into suburban areas or, in many cases, different countries.

In North America, and to a lesser extent in Europe, the dream of a detached home and green space exacerbated the dereliction of working-class neighbourhoods during the deindustrialisation of many cities in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. “The middle class fled the city centres as they became overcrowded and increasingly associated with social problems such as crime and drugs, and the building of highway networks made it possible to live further and further away from where you worked”, says Steven High, Professor of History at Concordia University in Montreal, Canada. “On the other hand, the opening up of huge swathes of former industrial and waterfront lands during this period enabled urban planners and private developers to regenerate inner-city areas”. Rampant inflation of rents in cities worldwide – a consequence of urban population growth – have been dictating an ever-accelerating pace of conversion, and in the meantime, factories that weren’t torn down have been progressively repurposed for all kinds of activities. Large industrial sites gave way to museums, creative hubs, startup incubators, wall-to-wall condominiums and company headquarters, while individual buildings were turned into restaurants, bars, shops and lofts.

“If those units were no longer in use, it’s only natural that we’ve found them new types of functions”, says Matjaz Ursic, Urban Sociologist at the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. Yet, perhaps ironically, considering that factories have been a symbol of uniformity and mass-production, industrial renovation sprang up in close association with creativity and experimentation. In late-1960s New York, artists led the way when they set up home and studio in former industrial buildings in New England and Lower Manhattan, attracted by the naturally lit, ample spaces then available at affordable prices. In the ‘90s, abandoned factories became a fertile ground for youthful exploration. “Urban explorers like Ninjalicious, who illegally entered abandoned spaces to take photos, were drawn to the profound sense of awe that they felt in these spaces – something I call the deindustrial sublime”, says High. However, if the constraints of urban sprawl and the lure of cheaper rents, in addition to a certain fascination with abandoned and historic sites, played a vital part in the early stages, the reuse of industrial buildings has since increasingly become a sensible choice, attached to a design culture.

Among the world’s most famous restaurants, Noma recently moved location – from one warehouse to another. Against a backdrop of skyscrapers, a triple-pitched-roof warehouse in Singapore recently reopened as a design-led hotel. In New York City, an industrial past lends appartments a particularly sought-after status. What’s the draw of the industrial aesthetic for a savvy 21st century audience?

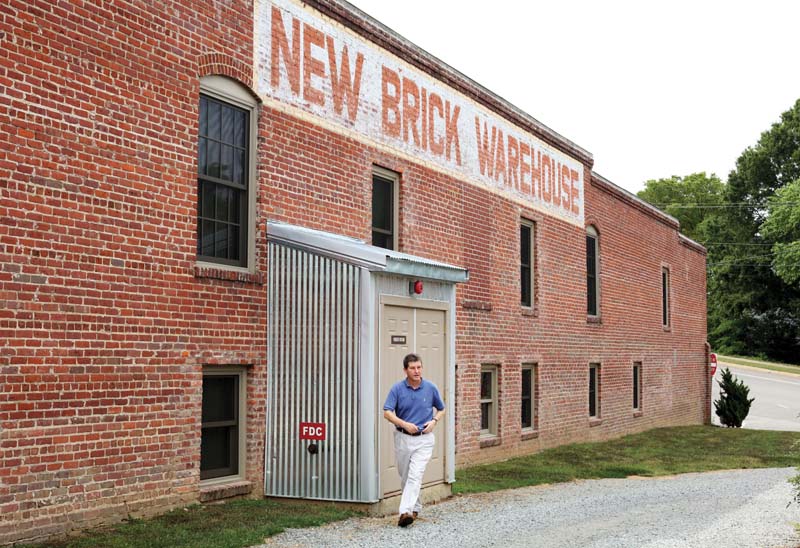

Part of the answer lies far back in time. Architecture has always been used as a means of displaying social importance – as evidenced by churches, public buildings, and royal structures – and at a certain point in the course of industrialisation, productive units followed. “Around the early 1900s, the factory was seen as a building type deserving of architectural treatment in order to enhance the production of goods and dignify the workplace, as well as forge corporate identities”, according to Ljiljana Jevremovic, a researcher at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Architecture of the University of Nis, Serbia. In Victorian London, powerful businessmen demonstrated their wealth through ornamented brick facades.

In every country of industrial heft, the commissioning of renowned architects to design factories became common practice, and many of those buildings show a masterful use of the materials and methods of the time, along with a thoughtful use of light and volume, including the characteristic large windows and high ceilings. Though assembly lines speak of harsh living conditions and evoke gloomy imagery, the industrial aesthetic emerged from a close link between architects, designers, and industrialists, as epitomised in the Deutscher Werkbund: an influential organisation founded in Munich in 1907 with the purpose of inspiring good design for mass-produced goods and architecture.

“Industrial forms, materials and aesthetics had a great influence on the direction of early modern architecture”, says Jevremovic. “Industry and its processes inspired and still continue to engage the imagination of artists and architects: from the voice against ornament by Adolf Loos to the design explorations of the Bauhaus and the sleek lines of the International Style to the explicit expression of construction elements in the work of Richard Rogers and his partners”.

In more recent times, renovation strategies in cities worldwide have further reinforced the link between industrial and creative. “The initial phase of an industrial conversion often revolves around temporary usages of the space”, says Ursic, “and welcoming artistic-led initiatives has become a prime strategy for rapidly revivifying an area. This type of initiative is very effective in rendering a cool label to a previously neglected area.”

The importance of artists in neighbourhood transition has proved so vital that some researchers have called them the “colonising arm” of the middle classes. The success of creatives in regenerating an area is, nonetheless, a double-edged sword, as they easily fall victims of gentrification, as do vulnerable parts of the local community.

Creative hubs – a perfect fit for large industrial buildings due to their need of open-plan, flexible spaces – appear to exist fundamentally in the in-between space, housed in short-use properties, before they are knocked down or converted. But if these spaces are often an issue of debate for their precarious and impermanent nature, their impact on visual culture is long-lasting. “The use of industrial sites for this purpose led an industrial aesthetic – a sort of steampunk look, old and futuristic – to become symbolic of the new cultural startup”, says Andy Pratt, Director of the Centre for Culture and the Creative Industries at City University London.

In a post-industrial society where the problematics of mass consumption and the use of resources are on the world’s agenda, the lure of an industrial aesthetic could seem puzzling. Yet, its perennial appeal touches on something else entirely: how creativity came full circle and cemented itself between exposed bricks and beams, under double-height ceilings.