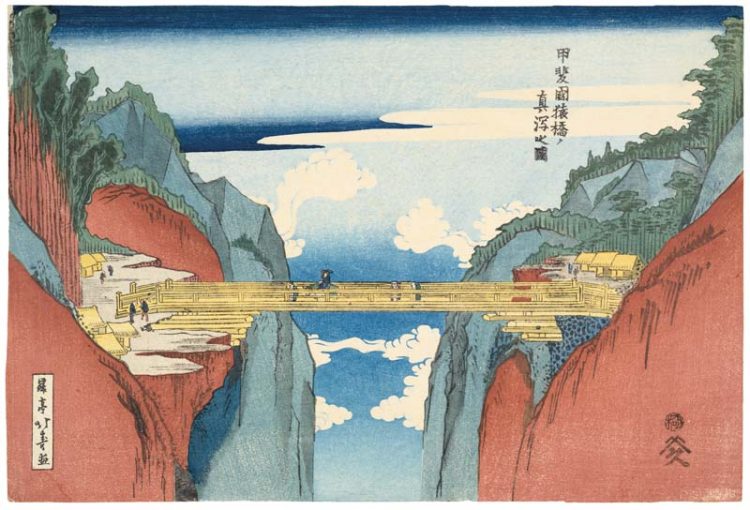

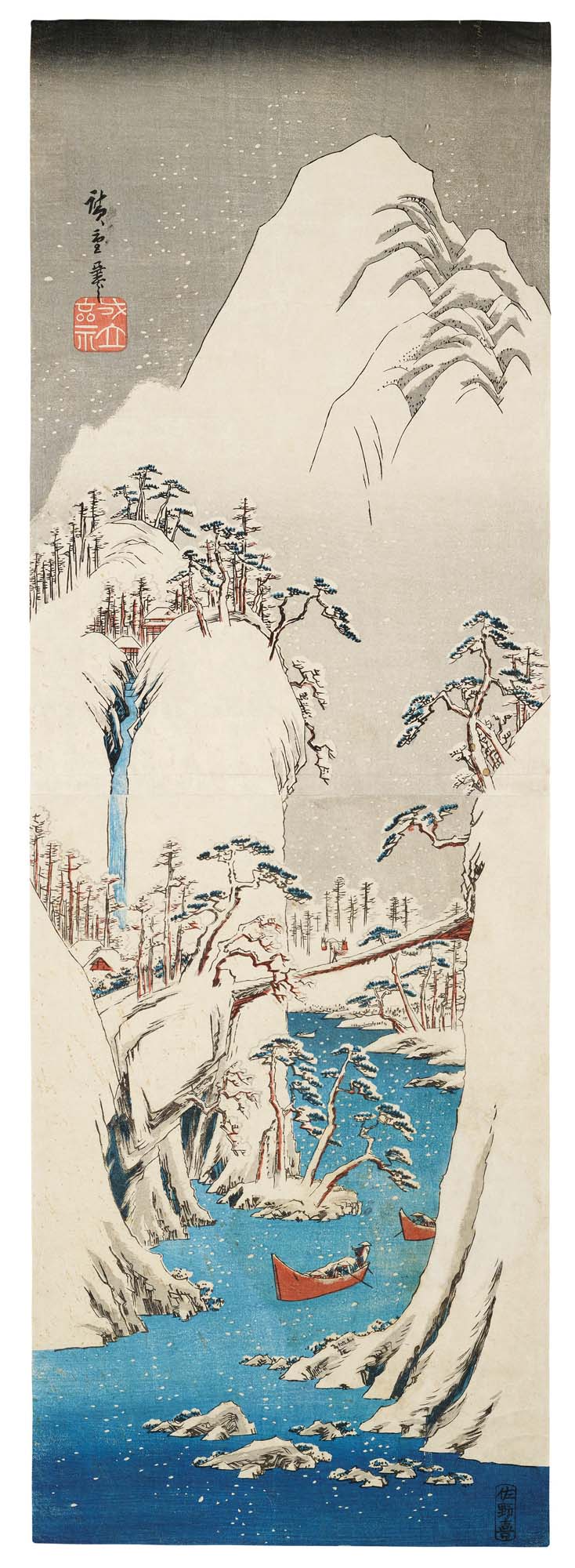

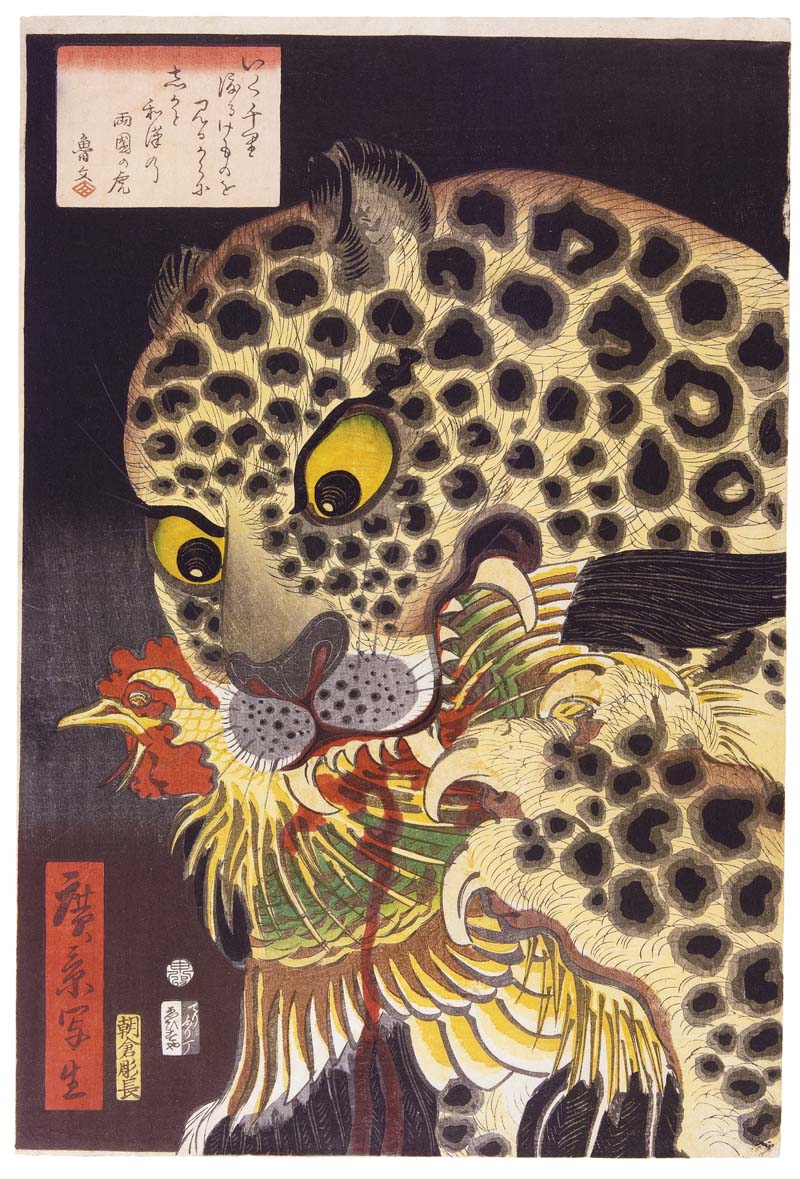

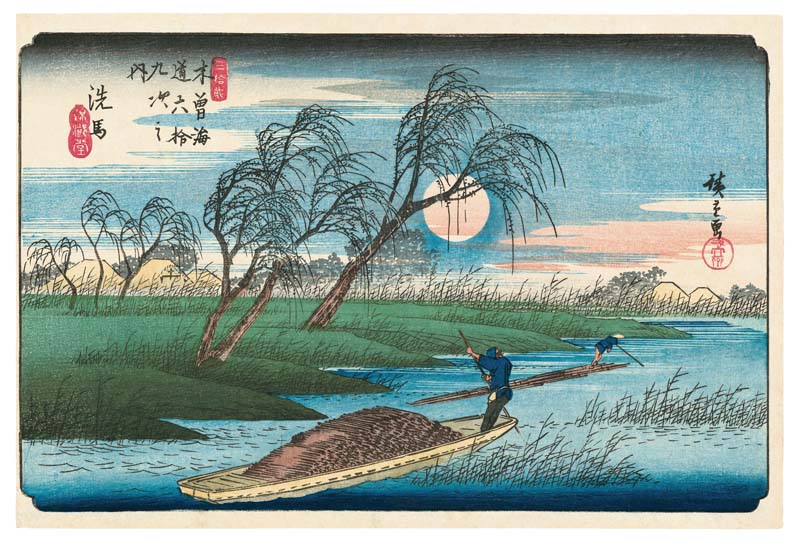

Giant catfish that terrorise fishing boats and upend entire oceans, samurai battling against writhing serpents, warriors facing off against enemies. Or quieter, more serene scenes: a boat gently guided down a river without a ripple; geigi chatting on a summer’s evening; the stillness of Mount Fuji.

The magic of Japanese woodblock printing is that it resists any singular classification, any particular time period, or any Western interpretation.

Certainly, Western creatives have admired it: Van Gogh described Japanese artists as being able to “draw a figure with a few well-chosen lines as if it were as effortless as buttoning up one’s waistcoat”; French novelist Émile Zola was a devoted collector and indeed, the craze for Japanese art and design in late 19th century France became so absolute that it was given the name “Japonisme”.

The practice began in 8th century B.C., a somewhat laborious process that involved a close partnership between artist, engraver and printer.

A new edition of prints from Taschen demonstrates that it was not until the 17th to 19th centuries, during the Edo period, that the art form took off. Becoming the foundation of ukiyo-e art, translated as “pictures of the floating world,” the period coincided with the invention of colour printing, artists revelling in the joy of producing the vivid scarlet of a geisha’s kimono, or a Klein-blue sea.

The themes, too, were vast. Spanning the powerful, the pastoral and the romantic, artists often battled against censorship typical to the period, as well as strict limitations on conspicuous luxury. Yet, their images have endured: spanning centuries, scores of different artists – and a uniquely, beautifully Japanese sensibility.