It started, as most cultural movements do, with an act of defiance. Street art was born in New York City in the late 1960s, when kids would scratch their names into walls. Soon, those scratches became paint, and crude tags became works of art. Some of the early taggers in that chaotic period turned into world famous artists, like Keith Haring or Lee Quiñones, whose work now hangs in galleries rather than on street corners. Many New Yorkers at the time saw the burgeoning movement as nothing more than vandalism. They would be shocked at the global acceptance it has now won. The art has spread out from New York’s five boroughs to become a global movement, embraced everywhere from São Paulo to Shanghai. But it has been Dubai’s takeup of the practice that has perhaps been the most unusual.

From the relatively new City Walk to the long established streets of Karama, it’s hard to travel anywhere in Dubai in 2018 without coming across pieces of large scale outdoor art. Take the Dubai Street Museum, where sixteen large murals cropped up around 2nd December Street, created by a host of global artists including German maestro Case Maclaim, and the Russian Julia Volchkova.

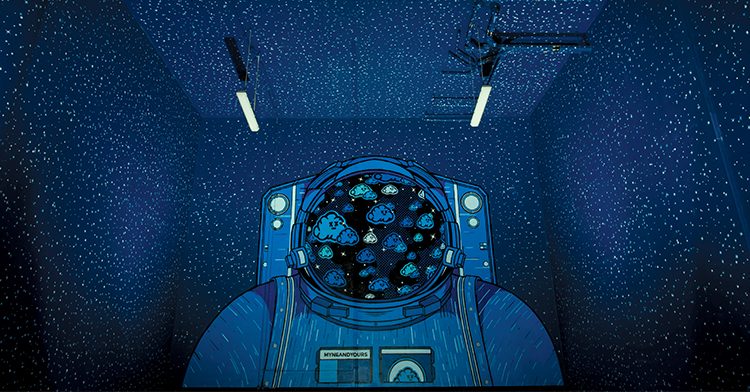

City Walk, a hip outdoor complex in Al Wasl, has also embraced the art form. Its developer Meraas brought in 15 international street artists to produce work as part of another initiative, Dubai Walls. The breadth of the work showed the possibilities this art form offers – from Blek Le Rat’s whimsical stencils to D*Face’s large-scale pop art. One of the most interesting pieces is from American Beau Stanton. He described his lenticular mural, which used the angular blocks of a building to create three separate perspectives, as one of the most challenging pieces he has ever created.

We have to ask what art can ‘do’ beyond money

The common thread running through these pieces? They were all commissioned. Aside from the odd tag here and there, street art in Dubai is very much a sanctioned activity – from the tourist board, perhaps, or brands hoping to to co-opt their coolness. For the artists, they get a blank canvas (how blank depends on the tightness of the brief) and, crucially, they get paid. It’s not just in Dubai that this is happening, and it can make for strange bedfellows.

In 2012, the European Central Bank gave €10,000 to a group of local artists to paint a fence that surrounded the renovation work on its new Frankfurt headquarters. Soon, the art began to criticise the ECB: outlandish caricatures of the ECB’s president and Angela Merkel appeared alongside critiques of the Eurozone and capitalism. Despite the inflammatory nature of the work, the ECB reacted positively, even buying one of the panels to hang inside its headquarters. The fence garnered huge media reaction, became a tourist attraction and showed the bank in a different light. Much of this, of course, is anathema to the purists, who still view the art form as something that should be a rage against the machine, rather than enabled by it.

Listen to the world’s most famous street artist, Banksy, who in an interview with Village Voice, said: “Commercial success is a mark of failure for a graffiti artist. We’re not supposed to be embraced in that way. When you look at how society rewards so many of the wrong people, it’s hard not to view financial reimbursement as a badge of self-serving mediocrity.” It’s easy, of course, to treat artists as somehow on a higher plane than the rest of us. But, like the rest of us, they need to eat too, and brands – in Dubai at least – provide a platform for artists to create and get paid.

You would be hard pushed to find an artist who didn’t welcome the city’s embrace of the art form. For Gary Yong, a Dubai-based, Malaysian-born artist, the city’s willingness to push street art makes sense. “Dubai has a strong consumer culture and it’s no surprise that brands will use street art to reach a certain demographic. It’s not a bad thing as it sustains artists, and they sometimes get to say something to the audience as well. It’s really up to both brand and artist to use the platform wisely.”

For Fathima Mohiuddin, a Dubai-born artist who runs creative artists services company The Domino, that means turning down a few jobs. “We do turn down a fair bit of work we get offered from brands. We try to avoid copying other artists’ work, painting just logos, working for free in exchange for ‘exposure’, that sort of thing. We try to make sure there is an actual original and creative requirement in the projects we take on. We do work to a lot of briefs but that isn’t always a bad thing because it does push you as an artist as well. So we look at projects that meet a client’s criteria but still inspire and challenge us creatively.”

And whether the work you see in Dubai was originally conceived in a brand manager’s office or the mind of a young spray painter, it’s hard not to be impressed. From City Walk to Satwa, Alserkal Avenue to Karama, street art serves multiple functions: at the most basic level it brightens the place up and helps keep the residents happy. It acts as a tourist attraction, and says to the world: we get it. A city that embraces street art (rather than simply painting over it) is a city that understands youth culture and the fact that what is defined as such, is constantly changing.

What hasn’t changed is the battle between commercial realities and the pure artistic sense of the people doing the creating. That, according to Mohiuddin, is inevitable. “In other major cities there’s public funding for local artists and projects around street art as part of community development projects. That hasn’t really happened in Dubai yet, though there’s talk about it, so the people spending the money on these projects are the corporates. What we try to do in working with commercial entities is to push for substance and integrity to stay intact.”

Commercial success is a mark of failure for a graffiti artist. We’re not supposed to be embraced in that way

According to Rollan Rodriguez of the Brown Monkeys, one of the region’s oldest street art collectives, it’s up to the artists to set their own boundaries. “Commercialism can be good in that it promotes artists and pays them, but usually the person paying decides on the subject matter. It’s up to each artist to decide what they are comfortable with and go from there.” The Brown Monkeys hark back to the graffiti crews of the late seventies and early eighties and, according to Rollan, “trust and brotherhood” drives the group. “When we get a new project, we instinctively know to whom the project will fall. We all select projects based on what excites us.”

It was inevitable that street art moved from the street to the gallery. Tucked amidst the white-washed villas and Bougainvillea of Jumeirah 1, the Street Art Gallery is the first in Dubai to focus on street art. Opened by Stephane Valici, a fifty-something French entrepreneur in 2013, the gallery is filled with work by the likes of Mr Brainwash and prints by Damien Hirst. With work costing from $600 to $10,000 plus, it’s not cheap, but it’s a good indicator of how far the genre has come, not least

in Dubai.

So what of the future? Mohiuddin believes that a focus solely on the bottom line isn’t healthy. “We have to ask what art can ‘do’ beyond money and that goes back to community development, outreach, education, awareness,” she says.

“Street art projects shouldn’t just be about flying in the biggest name or marketing strategies because it’s trendy. There needs to be more of an emphasis on what the community needs, and support for that, so there isn’t as much pressure to work with corporates and initiatives with more substance and social value can happen.”