“I’ll never forget my first experience of being in a race car,” legendary actor Paul Newman told an ABC documentary team in 1979. “The first thing that attracted me was the speed. That and the faint possibility that I might get good at it one day. It offered me the chance to be graceful, it just grabbed hold of me. I used to just slink off from doing pictures to try and get my [racing] licence.”

Newman received that licence in 1972 when he was 47 – an age when most racing drivers are comfortably retired. He came to the sport late after starring in the 1969 film Winning, in which he played an Indy 500 driver. Training for the role awakened a love of motorsports so intense it would come to dominate the rest of his life, setting him on course to not only compete in the world’s toughest endurance car race, 24 Hours of Le Mans, but very nearly win it.

Established in 1923 as a rugged alternative to the concentrated glamour of Formula One, this annual event requires participants to race for 24 hours through the streets of Le Mans with the winning team judged on a variety of criteria, including distance covered. Three drivers man each car, switching every two hours to eat and rest. Racing at an average speed of 105mph, drivers need incredible concentration, endurance and reflexes while the cars sustain constant buffeting from other vehicles as well as the wear and tear of repeatedly overtaking, braking and manoeuvring.

No wonder Le Mans was originally conceived as a proving ground for high-end road cars.

“Just two weeks after the first Porsche [356] was delivered in 1948, it went on to contest its first race,” says Hartmut Kristen, former head of motorsport at Porsche, the most successful manufacturer in Le Mans’ history with 16 wins. “In the 1950s and 1960s it was normal for a customer to drive his Porsche 356 with its numberplate to the track, take part in the race and then drive home in the evening.”

In his reliable Datsun 510, Newman got faster and faster, becoming arguably one of the best amateur drivers in the US

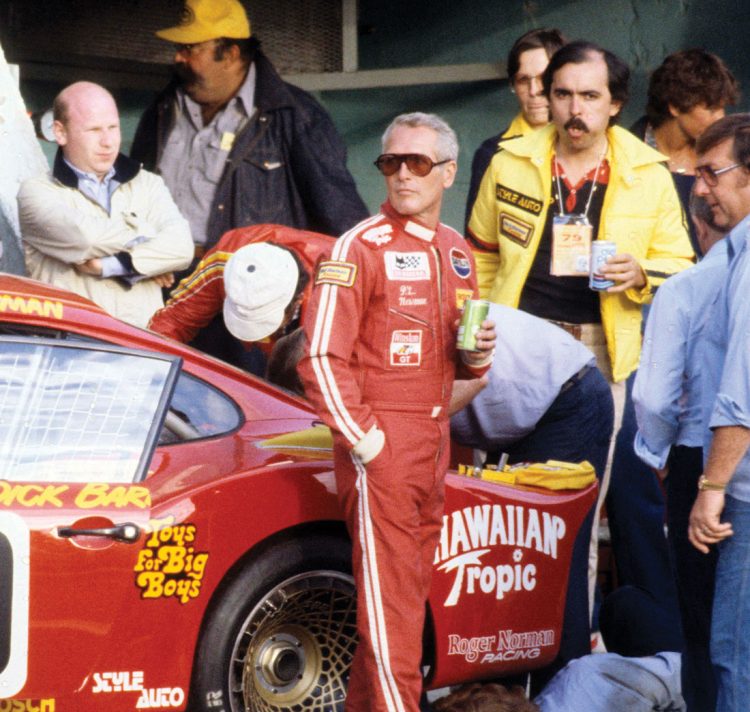

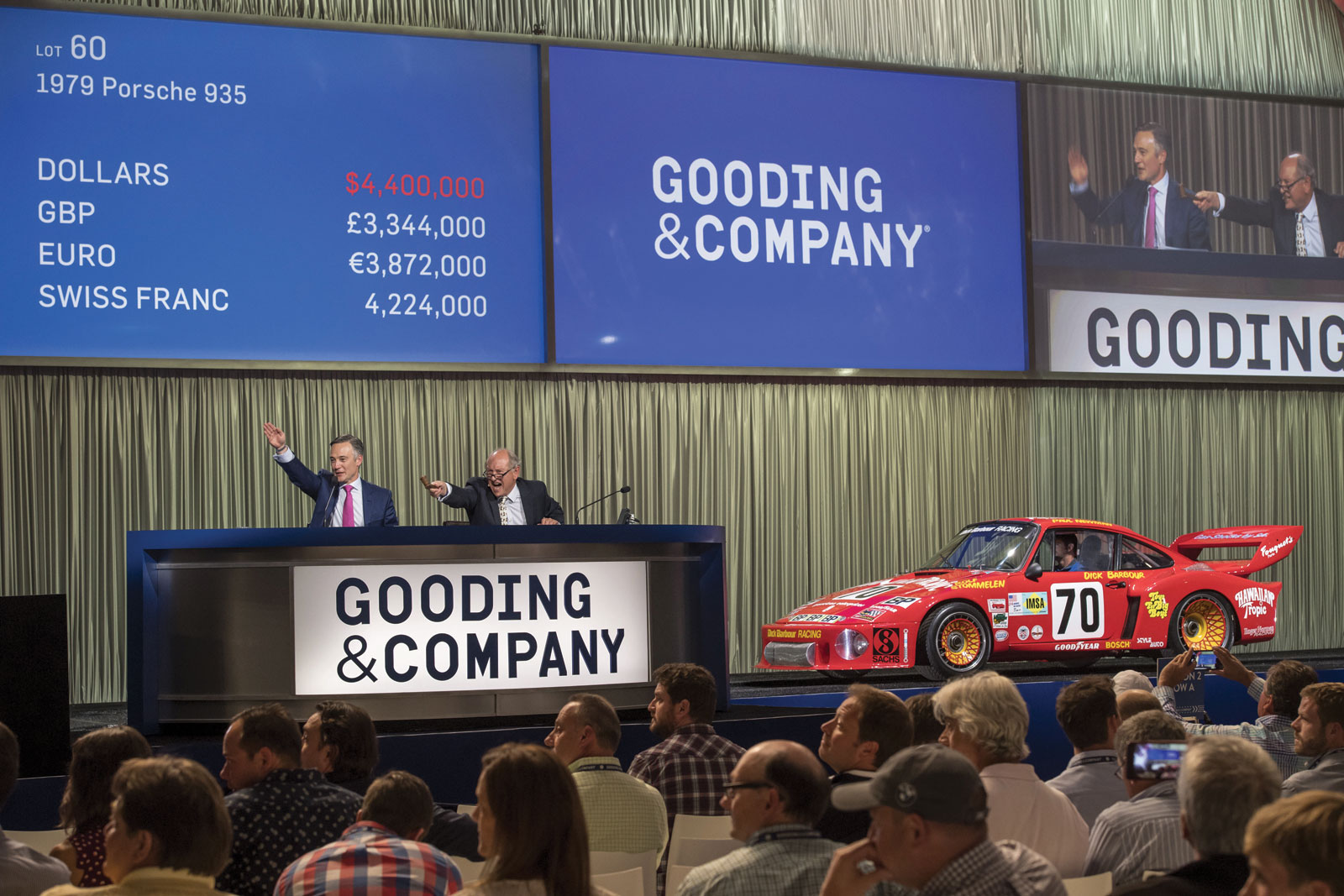

That was almost exactly what Paul Newman did. He was competing in a souped-up Porsche 935 that had been purchased by team owner Dirk Barbour, a Porsche dealer and racing enthusiast, who had bought the car to replace one he had crashed in his last race.

This might sound a little frivolous but it’s not surprising he couldn’t keep hold of it. The Porsche 935 was a monster. Stuffed with cutting-edge engineering, it came with a twin-turbo engine, large brake discs and the infamous upside-down gearbox. It handled like a saddled tiger but could hit 200mph on the straight. Of course, whether your teeth would be in your mouth at the end of it was a different matter.

These concerns were easily shrugged off by Barbour, who had been racing Porsches for years, and professional driver Rolf Stommelen was a four-time 24 Hours of Daytona winner. The question was whether it would be too much car for the rookie Newman, who had paid his dues in far more docile machines altogether.

“There was a Datsun dealer who lived seven minutes away from my house and who had a race team and ran in Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) races,” he told Australian newspaper The Age. “He had a really classy, sophisticated operation so that’s how I started, driving a little four-cylinder Datsun and just working my way up. There was no point in racing unless I really took it seriously, so that’s what I did.”

In his reliable Datsun 510, Newman got faster and faster, making a name for himself in the process. In 1973 he stepped onto the podium in five of the six SCCA races he contested, winning one of them. By 1979 he was racing in two SCCA classes as well as the more competitive IMSA series – pitting himself against a raft of young, talented drivers. He won 14 out of 16 SCCA races and enjoyed a flawless eight-race winning streak in the B-class sedan category.

He was arguably one of the best amateur drivers in the US but he wanted to move up a notch and saw Le Mans as the perfect opportunity to prove himself. Not everybody was convinced, most noticeably the cadre of agents, insurers, managers and money men who thought he was risking his career – and life – to pursue his hobby. They didn’t have to look too far back for evidence of how dangerous the sport was.

In 1955, Le Mans was responsible for the worst accident in the history of motorsports, when driver Pierre Levegh crashed at 190mph, killing himself, 75 spectators and injuring 120 people. The disaster brought the world of motorsports to its knees, instigating widespread reviews and safety practices that still define the sport, including mandatory use of seatbelts, more reliable braking systems and roadside barriers.

Another of these safety practices – scrutineering – has become one of the iconic features of Le Mans. During scrutineering drivers take everything, from the cars to their helmets and gloves, to the city centre where they are inspected to ensure they comply with the sport’s rules. Scrutineering days are published in advance so that the public can attend, lending a festival atmosphere to what’s really a dry, administrative task.

“At any other track, scrutineering is in the pit lane. It’s private, behind closed doors,” says three-time Le Mans champion Alan McNish. “It’s not in front of the town and passers-by. At Le Mans, it’s when the fans can get close to the cars, to the drivers, to the entire atmosphere. There’s no other sporting event in the world like that. It’s one of the little quirks that makes Le Mans special.”

More than anything else, scrutineering is responsible for turning the race into the iconic tourist attraction it is today. Over race week, 175,000 people descend on the town, flowing through its bars and restaurants, filling its coffers before vanishing again when the race ends. Part of this money is used to maintain the old town of Vieux Mans and, as a result, it’s a perfectly preserved slice of medieval history, its castle presiding over twisting lanes and a crush of medieval French houses. It’s an ideal balance. This most modern of sports helps pay for the preservation of the past, ensuring an influx of culture-minded visitors when the race is over.

Unfortunately, it was this popularity that put an end to the 54-year-old Newman’s Le Mans career. His team finished second behind the Porsche-backed Kremer team, which was driving a heavily modified version of the Porsche 935. It was a good result but after the race Newman admitted he and Barbour “didn’t drive too well today”, forcing Stommelen to continually make up seconds whenever he got into the car. As the old Le Mans saying goes, “you don’t need good luck, just to avoid bad luck” and Stommelen couldn’t do it all day. A blown gasket toward the end of the race kept the car in the pit longer than they’d intended and it never really recovered. They limped into second place with a dying engine as Kremer sped away, finishing 59 miles ahead of Newman, Barbour and Stommelen.

In any other race, this near-miss might have been enough to prompt Newman to try again but the actor found everything about the experience exhausting. In US races he wasn’t treated like a movie star. He’d earned the respect of other drivers with his dedication to the sport and they helped keep the photographers, press and fans away. Le Mans was something else. The world-famous actor at the world-famous race brought crowds from the world over and there was nobody to keep them at bay. Newman was swamped everywhere he went, popping bulbs and autograph hunters interrupting team meetings and training. “I’m getting a bit long in the tooth for this,” he would later tell The New York Times. “And my racing here places an unfortunate emphasis on the team. It takes it away from the people who really do the work.”

Describing himself as feeling like a piece of meat, he vowed never to contest Le Mans again and was true to his word, although he would carry on racing until he was 82, forming his own team and pumping millions into the sport he loved.

Words: Stuart Turton